My friend Ray and I went looking for adventure and got more than we bargained for.

When I got back from Newfoundland, it was the end of July and I was already starting to think about teaching. More accurately, I was beginning to dream about teaching. (My school begins mid-August, unlike most universities that begin after Labour Day.) I get these dreams toward the end of summer. In them it’s the first day of the semester and I’m not ready—my outlines are still at the printers, my textbooks aren’t in, I’m running late and can’t find something I need in the office, and when I arrive to class, a senior respected colleague is sitting at the back, having decided to audit my course. That kind of thing. I thought I was the only person who got them, but apparently they’re so common among teachers that they’re called Teacher Dreams. Anyway, I was already getting them so decided I’d put off that second planned trip to The States and the BDRs until the following summer and use what little time there was left in my summer vacation period to do shorter trips.

I asked my buddy Ray if he’d join me in doing a local overnight adventure ride. Ray likes the big gleaming classic bikes and rides an Indian Chief Vintage, but we won’t fault him for that. He’s also got a 2003 KLR in army green and joins me on off-road adventures when he’s feeling especially masochistic. We’ve had some adventures in the past, usually involving a hydro line, water, mud, and something semi-legal, so I think he was a bit reluctant. But I assured him I’d find something mellow this time, and like the good sport he is, he agreed, so I started researching the ride. The idea was for a relaxed dirt and gravel ride that had some nice scenery in the mix.

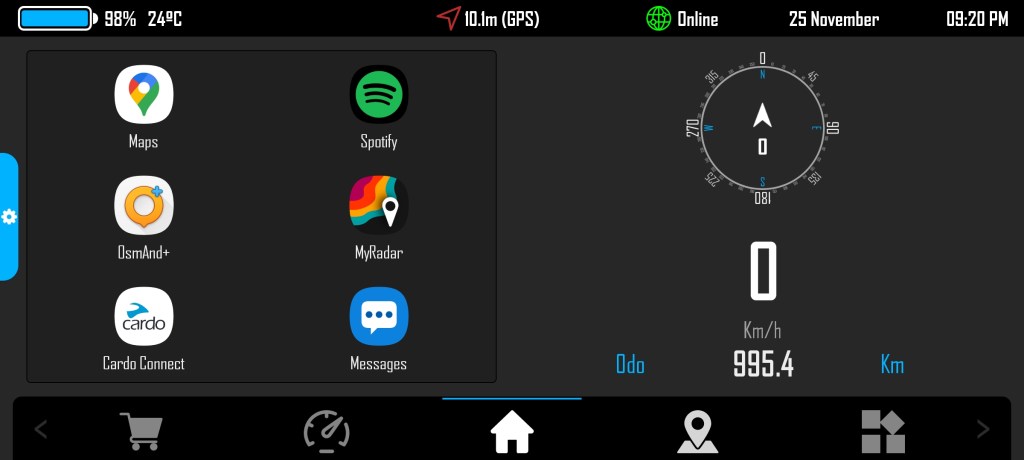

My first choice was The Bytown Adventure Loop and went as far as to pitch it to my editor at my paying gig, northernontario.travel. It’s always nice to ride, even better when you get paid to do it. The Bytown Loop was announced a few years ago to great fanfare, including a whole YouTube video to present it, and it looked pretty perfect for our purposes—big-bike friendly, close to home, with food and accommodations available should we want to avoid camping and cooking. Easy peezy. The only problem is that I couldn’t find the GPS files anywhere. You can see my query on the YouTube page, with no response. Same when I asked the channel owner directly. Hmm . . . seems like a lot of work went to waste at the final stages of development or there’s something I don’t know.

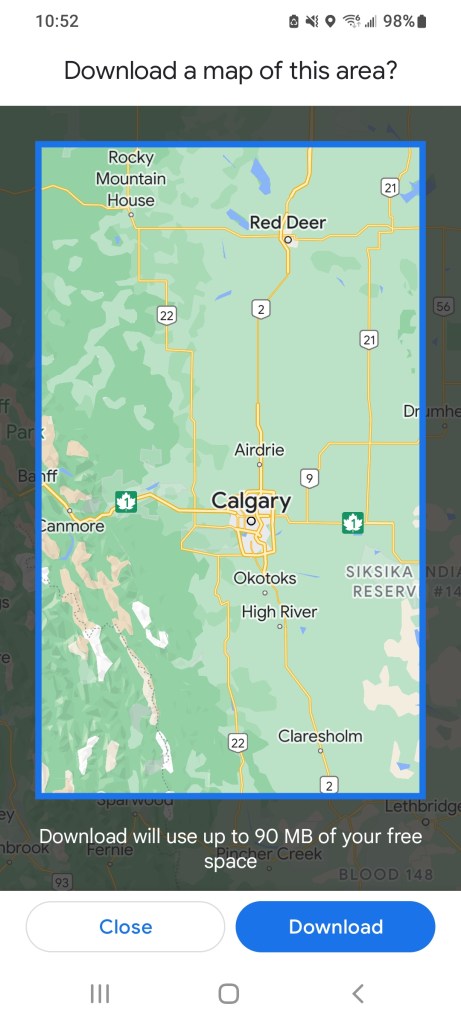

A little more sleuthing brought me to GravelTravel and he has lots of files available for a small fee, including the TCAT, and another that caught my eye, the Ottawa Valley Overland Route. It seemed similar to The Bytown Loop so I checked it out on YouTube. The videos I saw looked pretty mellow—apparently a large section of it is on abandoned railway line, which is usually flat, straight, and easy. Forums did not reveal anything concerning. In fact, I saw one post asking if it could be done in a non-modified AWD car, so I thought we’d give it a go. It would mean camping and cooking, but to be honest, I prefer that to venturing into town. I bought the files, reserved a campsite at Granite Lake, about halfway through the loop, and bought Lanark County trail passes for Ray and me.

The route is listed as 2-3 days. We were going to do it in 2, which was a bit ambitious since it would take us 1.5 hours to get to Merrickville, where we would pick up the route. To make matters worse, no sooner had we begun when we had a delay. We had done some service on Ray’s bike earlier in the summer and as we rode toward the Ontario border I began to doubt that we had re-oiled his K & N air filter. I remember washing it, and setting it out to dry . . . but not oiling it. You really don’t want to run those filters dry at risk of damaging your engine, so when we reached Alexandria, we pulled into a Tim Horton’s and discovered that yes, it was dry. Thankfully, the ubiquitous and life-saving Canadian Tire there had a K & N maintenance kit so we oiled the filter and let it sit while we had our coffees. It was a small delay, but on a tight schedule, every unplanned stop costs you dearly later on.

Merrickville is a charming historic village with more heritage buildings for its size than any other town in Ontario. I’ve written about it as a favourite destination for bikers here, but in this case we were just passing through. Soon after lunch, we picked up the OVOR track and, to my great surprise, almost immediately hit mud.

I didn’t have the tires for mud. I still had on Dunlop Trailmax Mission tires from my tour, so I stopped to assess the situation. I was also thinking of Ray, to whom I had promised an easy ride. I waded in and it wasn’t deep, just a bit slippery. I looked at the map and it appeared to be a short section. Now in this situation, Clinton Smout advises to let your buddy go first, but since I’d got us here, I figured I was the test probe. Ray got out his phone to catch any action.

“It’s not bad”? Soon I’d be eating my words when my tires caked up. Some of this easy trail wasn’t so easy.

The Tiger doesn’t have much low-end torque and I have to keep the revs way up whenever off-roading or it stalls. Soon after this ride I did my valves and all the exhaust valves were tight. I’m hoping that opening them up will help with the stalling. A little further on we turned left onto some two track, crossed a swamp, and popped back out onto gravel.

Once back on the road, it was smooth going again up into Carlton Place, another pretty town that was on my Top 5 Ottawa Area Destinations list.

We filled up in Almonte before heading down into the bush south of Ottawa. The highlight of the day was riding the Lanark County Trail System south of Ottawa.

I was loving this and could have done it all day! The Tiger is in its element here and the Tailmax Mission tires are fine for this stuff; the back end slides out but consistently. We stopped for a photo out over White Lake during the golden hour and the ride was now everything we were hoping it would be. We had a little ways to go to get to our campsite and were looking forward to the steaks I had packed in one of my panniers.

Sadly, the fun would come to an end too soon. We crossed a hydro line, then rode the line for a few hundred metres before exiting onto another gravel road. Unfortunately, what we didn’t know is that the bridge crossing the river that feeds into Duncs Lake was under construction and was out. We got off our bikes and surveyed; sometimes you can find a way through even if it’s closed (the semi-legal stuff I alluded to earlier). In this case, that wasn’t possible at all, and we happened upon a workman finishing up his day and he confirmed what we already knew: end of the road. (What was especially frustrating is that they were building a new road called, appropriately, The New Road, and it was smooth sailing on the other side. We looked at our map and figured we were about 2 kilometres from Highway 511 and the best bet was to return to the hydro line and follow it out to the road.

Hydro lines. When you’re stuck in the bush, they’re a lifeline to civilization, a man-made geometrical order imposed on the chaos of wilderness. But they can also lure you into that chaos, the fisherman’s line drawing you into dark waters. And speaking of water, what I’ve found is that they almost inevitably involve some of it at the low points as the terrain rises and falls. A ride along the primitive access trail of a hydro line is a rocky descent to a water crossing to a steep rocky hill climb to a moment of respite before another descent, and on, for hundreds, thousands of miles if you want, from dams to urban centres, traversing great swaths of Canadian boreal forest.

We got through that without incident but by now it was getting late, we were getting tired, and our off-road skills were suffering as a result. I offer these two videos for your amusement, at our expense.

Ray took his own tumble and decided, while down there in the tall grass, to take a little nap.

In the first video, you can hear concern in my voice. I was worried that we would come upon a crossing that was just too deep to cross and that would block us from the highway. At this point, I was getting some serious arm pump and had pretty much given up on making it to Granite Lake and our planned campsite. We’d figure out where we were going to spend the night once out of the bush.

But we never made it that far. At one water crossing, I got hung up on some rocks and dumped the bike. I hit the kill switch before it dunked but the bike wouldn’t start once righted. After trying for a while, I left it sitting there while deciding what to do.

Eventually, we ended up just pushing the bike out by hand and it was surprisingly easy. But it wouldn’t start, no matter how many times I cranked it. Thankfully, Ray got across without incident. I have to say, the KLR really showed its capabilities on this ride. Where I was struggling on the Tiger, Ray was getting over stuff using the tractor factor of the KLR.

I figured the Tiger was hydrolocked, but to get to the spark plugs on this machine you have to remove a lot of plastics and lift the gas tank. I didn’t want to start that work with 30 minutes of light remaining, so we made the decision to camp on the hydro line. I left my bike where it was, Ray rode his up to a clearing on the line, and we set up our tents there. I fired up my stove and cooked us the steaks. We had a little something from the liquor store in Alexandria, and I had a pipe and Ray had a cigar. It wasn’t exactly the campsite at Granite Lake I had imagined, but we made the best of a bad situation.

That night in my tent I had a restless sleep, worried that I might not have packed the spark plug socket. I wasn’t sure because it’s such an involved process to access the plugs that I might have concluded I’d never be lifting the tank trailside. But thankfully I had, and after morning coffee and porridge, we started tearing apart the Tiger.

In this photo, you can see a section of hose coming out of the bottom of the tank. That is a hose I carry for emergency syphoning should someone run out of gas. We found that when we lifted the tank, gas flowed out of the overflow drain. I’ve had that tank lifted before and it’s never done that. It was a clue that I should have paid more attention to.

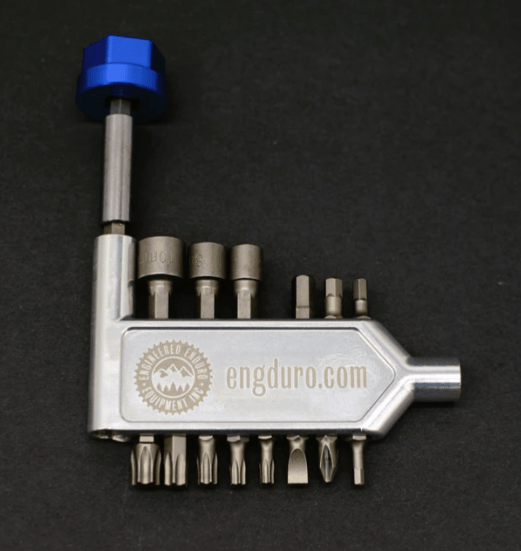

We took out the plugs and they looked dry. We turned the engine over and no water came out of the plug holes. Next we thought that maybe the air filter was soaked and choking the engine. Unfortunately, Triumph put a weird 7mm hex screw on the airbox and I didn’t have that socket on me. I pride myself on being prepared but I came up short on this occasion.

We decided that I would ride Ray’s KLR out and up to the Canadian Tire in Renfrew. Why me? Ray said I had more experience off-roading and would have a better chance of getting out. There was some really gnarly terrain and a pretty significant water crossing, but I made it out, again, impressed by the KLR’s capabilities off road.

Shortly after I started heading up toward Calabogie, the skies opened up and it started to rain cats and dogs.

It was weird weather. In Renfrew it was dry with blue skies. Little did I know it was still coming down hard back on the trail. Canadian Tire had the 7mm deep socket, and while in town I picked up lunch and water and gassed up Ray’s bike. I was planning for the worst case scenario.

As I rode south on the 511 toward the trailhead, I rode back into the torrential rain. It was bad! In fact, unbeknownst to us, this extreme weather was causing major flooding in nearby Ottawa and back home our wives were concerned. I got to the trailhead and started heading back in, but before I reached the bike, who did I see walking out but Ray. He was soaked to the skin and looked pretty miserable. Our “easy ride” had turned into 24 hours of hell, stuck in the bush in extreme weather. I was never going to live this down.

Ray had determined that the trail was now impassable and that I might be waiting for him at the highway. I guess he doesn’t know me as well as I thought. No extreme weather was going to prevent me from getting back to my bike. But he looked cold and miserable and it was teeming, so we agreed to abandon the troubleshooting and get a room in Calabogie. There was nothing more to do but turn around and splash Ray, who couldn’t get any wetter, then double him out to the highway.

Unfortunately, he had started walking without his helmet, so I doubled back, tidied our gear, grabbed his helmet and jacket, and returned to ride us up to the Calabogie Motel.

It was sunny in Calabogie but probably still raining 20 kilometres south on the trail. I didn’t feel very good about leaving my bike on the trail overnight but tried to put it out of mind. We went for dinner at The Redneck Bistro.

The next day we were up and out early, eager to get the airbox open and hopefully solve our problems. I’d been communicating with my buddy Riley from The Awesome Players, who has more experience with bikes than me. He too was confident that when we got it open, we’d find a soggy filter and after drying everything out the bike would fire right up again.

The trail was still waterlogged and I was worried about doing the deep crossing again. We didn’t need two hydrolocked bikes. But the KLR is a beast, and I told it so.

Things went a little sideways on me there but we got safely across. I left his bike at the top before the gnarly stuff, then walked down to the bike. With great anticipation and suspense, I got out the new 7mm socket and opened the airbox . . .

It was dry, bone dry. I was deflated. Ray had been walking in from the road and soon arrived. We continued our troubleshooting but were running out of ideas. We tested the plugs and there was spark. We took out the filter and the Unifilter prefilter. We checked all the fuses. The one for the auxiliary socket was blown and we thought we’d solved it then, but after replacing it, the bike still wouldn’t start. We looked down inside the throttle bodies for water. We inserted twisted paper into the throttle bodies and it came up dry. We put a drop of fuel from my stove bottle into each throttle body and still it did not fire! Not even a cough.

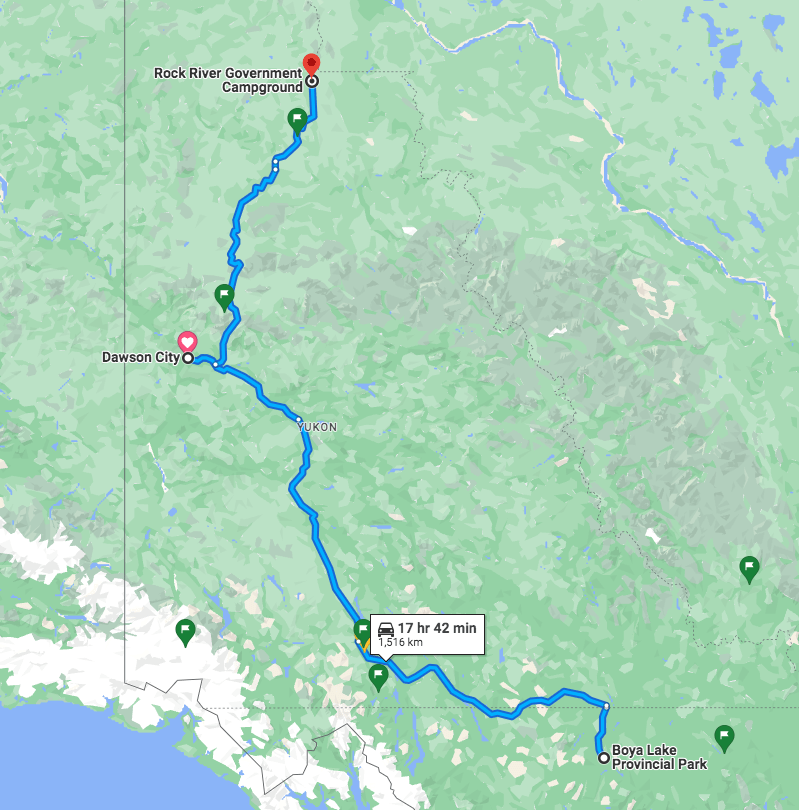

As a last resort, I walked up to where there was reception and called Riley to see if he could think of anything I hadn’t. He asked if I could hear the fuel pump cycle on with ignition. I did. He said he’d consulted with Player Ivan and it didn’t make sense: we had fuel, we had air, we had spark—the bike should run! We were all stumped, and with it already getting on the afternoon, I decided to throw in the towel. I didn’t want to spend another night on the hydro line and knew there were limits to what I could ask of Ray. Riley offered to trailer me back to Montreal if I got the bike out of the bush. So we took Ray’s bike again and rode back into Calabogie where I found someone who does trail rescue. It cost me a pretty penny but I was out of options.

Back in Calabogie, Riley and his brother arrived and we loaded both bikes onto their trailer and headed for home.

I will admit I was feeling more than a little deflated on the drive back to Montreal. It reminded me of when the water pump went on the 650GS while at Dirt Daze and, for a moment, I considered selling it for something more reliable. Perhaps Riley knew what I was thinking and told me about Super Dave’s mint 1200GS he got for a song.

And I was disappointed in myself. How could I ride into remote areas if I couldn’t be sure to get myself out? It felt like, after all my preparation over the preceding years to learn about bike mechanics in order to do that kind of riding, I’d been tested and had failed. I also felt bad for Ray, who had suffered hypothermia and water-damaged his phone. When I got back to Montreal, I stuck the bike in the shed and couldn’t bring myself to touch it for a few days.

When we are at our lowest, it’s our friends who lift us back up, people like Riley who drove out from Montreal to fetch me, and my buddy Mike who came by to shake me out of my doldrums and help troubleshoot the bike. He noticed almost right away the presence of water around the fuel line in the way the fuel was beading on parts, and we decided to drain the tank. I make home-brew beer and had an empty carboy to use. This is what we found in the tank.

Gas and water are insoluble and water is heavier than gas. This is a 23 litre carboy so I estimate that there was at least 3 or 4 litres of water in the bottom of the tank, and since the fuel pump draws from the bottom, the bike wasn’t getting any fuel. No wonder it wouldn’t start!

How did the water get in the tank? The fill cap seal is good, so it didn’t get in there. The bike was running fine up until it wasn’t, so I didn’t get bad fuel in Almonte. No, the only theory that makes sense is this: at the river crossing, the engine and tank were hot. When I dunked the bike, the tank cooled rapidly, creating a vacuum, and water was siphoned up through either the tank overflow or breather tube that was hanging in the water. It would only take a bit of water to foul the injectors and prevent firing, but with this much water in the tank, now I think the bike was drinking water the entire time it was in the river.

I’ve posted this theory on ADVRider to see if anyone else has experienced it and no one said they had, but I did find some threads on ATV forums supporting it. There’s supposed to be a check valve that prevents water or sand entering and also serves as the tip-over sensor. It’s a simple ball bearing valve, but I haven’t been able to locate it on the Tiger. The solution, I think, is to reroute the tubes to a higher point. This is what the ATV guys have done. You don’t want to just cut the tubes because you don’t want fuel draining onto a hot engine, so I’m thinking I will run them back along the frame toward the rear of the bike and have them drain somewhere safely behind the engine.

I’d be very interested to hear what others think about this. I’m surprised more bikes don’t have this problem, which makes me wonder if it’s particular to the Tiger or my bike. I’ve seen guys completely submerge their bikes and they don’t get any water in the tank, so what goes? If you have any ideas, drop a comment below. I’ll be getting out to the shed in the coming weeks to do a bunch of work on the bike in preparation for the season, and I understand there are some water crossings on the MABDR.

Anyway, Mike and I removed the fuel pump and squeezed as much water out of the filter as we could, then let it dry and reassembled. We purged the fuel rail and I changed the spark plugs. With clean fuel, the bike reluctantly started, first on two cylinders, then three. I added some Seafoam to a tank of gas and gave it the Italian tune-up all the way to Cornwall and back. Now it’s running great again. I also put in some cheap oil for a few hundred kilometres, then drained and refilled with the good stuff, just in case some water got in the oil. The bike is running fine now, especially since doing the valves. I feel better for having an explanation for what happened and am no longer thinking of selling it.

Some people say that the essence of adventure riding is adversity. We watch Itchy Boots riding through Nigeria and Cameroon with their bad roads, bad gas (if you can find it), security check points and security risks and are impressed by her courage. On the other hand, there are lots of people in my club who just want to ride and skip the adversity. I remember Ray once said at a club event that “riding with Kevin makes you feel alive,” and I’m reminded of what D. H. Lawrence once said along the same lines, something like, “Only once you’ve accepted death can you truly live.” I’m paraphrasing, but I think I know what he’s on about: if you don’t face risk, you are only existing, not living. I don’t go seeking danger—I love life too much—but neither do I let “what ifs” stop me from living the life I want to live.

Memento mori. When I’m old and feeble and no longer able to ride a motorcycle, I’m sure I’ll be thinking wistfully of Ray’s and my Ottawa Valley Extreme Weather Misadventure.