I left Katahdin Shadows Campground in central Maine after breakfast. I was looking forward to my ride along Highway 2 and to getting home and seeing my wife and dog. The trip had been full and exciting, but also exhausting, and I was ready to sleep in a bed.

I came out on the 157 and headed down to Highway 2. I can’t remember what signage was at that T-junction but somehow I turned the wrong way. Looking at it on a map now, I can only imagine that the options were 2 North and 2 South, and I, naturally, took north. Only I was supposed to take south, which is counter-intuitive since I live in Canada and was south of the border. But because the 157 intersects the 2 at an odd angle, I think that must have been what deceived me.

After riding happily for an hour, I came to a split in the road, with 2 and 2A as the options. This doesn’t look right, I thought, and checking my GPS, discovered I was further from home than in the morning. Yes, I’d been going the wrong way; I had to go south first before I could go west. I’d lost the morning and my GPS was saying I was 12 hours from home! Damn!

Knowing I was now in a fix, I changed the settings on my GPS from “Avoid Highways” to “Fastest Route.” It promptly took me to the I95 and I bombed south for what seemed like an hour and a half until I came to Augusta, which I recognized from my ride down. I knew I was now near the section of Highway 2 that I wanted, but getting through Augusta to that road was not easy. If I hadn’t had that GPS, packed almost as an afterthought (thinking I could “easily” navigate by paper map in the US), I would have been in a bigger fix. Maine’s road system resembles a spider’s web, and getting from Point A to Point B involves passing through Points R, M, X, and C first. Clearly, the Romans did not make it out to Maine.

Now finally on a road that looked familiar, I stopped for lunch at a roadside general store that also contained a diner. Knowing I had a long way to go, I powered up with a cheeseburger and fries. Then it was the long ride back along Highway 2 west out of Maine, across New Hampshire, and into Vermont.

Riding for me is like running. When I ride or run, I’m very meditative. Perhaps some people would say I should give the road my full attention, but I’m still concentrating on the road even if part of my mind is wandering, reflecting, processing, purging. I’ve had some of my best ideas while running or riding. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never worn ear buds or installed a radio in my helmet; for me, that meditative quality, that state of mental calm and presence is part of what I find therapeutic in both activities.

And similarly to when I ride, when I pass by a section of road that I’ve run recently, because my thought was so present in the moment, I can remember exactly what I was thinking at a given place. It’s like each particular of that geography has a thought attached to it, like the mnemonic to remember a poem by heart in which you think of a very familiar place, say, a local park, and as you walk though that park in your imagination, you associate a line of poetry with a particular object, a specific tree or lamppost, for examples, so remembering the poem later becomes merely a walk in the park, so to speak.

I’m mentioning this now because, as I rode west along Highway 2, I was remembering my thoughts and feelings vividly from when I rode east that section of road 12 days prior. All the feelings of expectation and promise and adventure came back to me even though my trip was almost over. And I remember feeling, I admit, a little apprehensive as I ventured out on my first long trip, not knowing exactly how it would go, what kind of problems I would encounter, and if I’d be able to solve them. But it had gone well and I’d managed; in fact, I’d done better than managed. I had ridden over 5,000 kilometres and met some wonderful people, seen some beautiful places, and learnt some new skills on the bike. What had I been so apprehensive about? Rather than a sense of sadness for my trip coming to an end, I had an urge to get back on the road again as soon as possible. Realistically, that won’t be until next summer, but I was already starting to think of where I might visit next year.

I turned north on the I91 that took me to the border at Stanstead, then I was on the familiar bumpy, pot-holed roads of Quebec. The 55 took me to the 10. The light was fading, and as I approached the Champlain Bridge the Montreal skyline rose up on the horizon. It was Saturday evening so the traffic was heavy, everyone driving in to town from the south shore. And then something else familiar: the winding tunnel of construction pylons lining the makeshift highway, lane-closures, douche-bags cutting in at the last moment at those lane closures, the ramp to the 20 Ouest unexpectedly closed, forcing me up the Decarie Expressway to loop around at Queen Mary (or was it higher?), then more lane closures on Decarie south, heavier, aggressive traffic, someone angrily leaning on a horn. It was all sadly too familiar.

I was pretty exhausted and now did have to devote all my attention to the chronically disrepaired and clogged roads of Montreal to get these last 20 kilometres home. I found it ironic that in the over 5000 kilometres I’d ridden the past two weeks, I never felt as unsafe as on those familiar roads so close to home. Once I was finally on the 20 Ouest after my detour and breathed a sigh of relief, some idiot cut across three lanes in front of me, passing a few feet from my front tire, his buddy close behind doing the same, getting off at the 13 probably to go to Laval. There are some things I love about this city, and some that I hate.

I always remind myself at the end of a long ride to concentrate right to the very end; I know it’s easy to lose your concentration and that’s when an accident can happen. But even knowing this and reminding myself in that final stretch of highway did not prevent a near accident on one of the last turns of the trip. As I came down the Des Sources ramp in 3rd, I went to shift into 2nd for the curve at the bottom of the ramp as I have done a hundred times, only when I shifted into 2nd, for some inexplicable reason, I forgot to pull in the clutch! What the hell?! The bike lurched and I immediately pulled the clutch and coasted. I found the bike in neutral and upshifted to 2nd, then took the curve, apologizing profusely to Bigbea. I can only think that these kinds of slips happen because you are already thinking of what you’re going to do when you get home. Another lesson learned: concentrate to the very end means to the very end. I think in the future I will associate the end with kickstand down, the signal that my brain can shut off now, or turn its attention elsewhere. Like my wife and dog that greeted me on the driveway. 😊

As I started the bike again when we shored, my gas light came on. I was surprised because I thought I had about another 90 km left in the tank, but then remembered I was off by 50 km. My bike doesn’t have a gas gauge, so I have to keep track of how much gas is left in the tank by using the trip odometer; every time I fill up, I reset it so I know where I’m at. At least, that’s what I always intend to do. For some reason, often I forget this crucial step in the filling process. I don’t know why; it just hasn’t become habit yet. And often there’s a distraction of some sort—the receipt doesn’t print, someone starts asking me questions about the bike, I’m dying to take a piss—and only remember after I’m back on the bike riding. Then I have to reset it while riding, which obviously isn’t ideal.

As I started the bike again when we shored, my gas light came on. I was surprised because I thought I had about another 90 km left in the tank, but then remembered I was off by 50 km. My bike doesn’t have a gas gauge, so I have to keep track of how much gas is left in the tank by using the trip odometer; every time I fill up, I reset it so I know where I’m at. At least, that’s what I always intend to do. For some reason, often I forget this crucial step in the filling process. I don’t know why; it just hasn’t become habit yet. And often there’s a distraction of some sort—the receipt doesn’t print, someone starts asking me questions about the bike, I’m dying to take a piss—and only remember after I’m back on the bike riding. Then I have to reset it while riding, which obviously isn’t ideal.

Sites are administered on an honour system at a whopping $21.60 a night tax included. They are grassy and private and quiet. If you’re ever in the area, be sure to stay at Boylston. She then proceeded to tell me where to find a micro-brewery pub with “the best fish and chips in the province.” If I hadn’t already been married, I might have proposed.

Sites are administered on an honour system at a whopping $21.60 a night tax included. They are grassy and private and quiet. If you’re ever in the area, be sure to stay at Boylston. She then proceeded to tell me where to find a micro-brewery pub with “the best fish and chips in the province.” If I hadn’t already been married, I might have proposed.

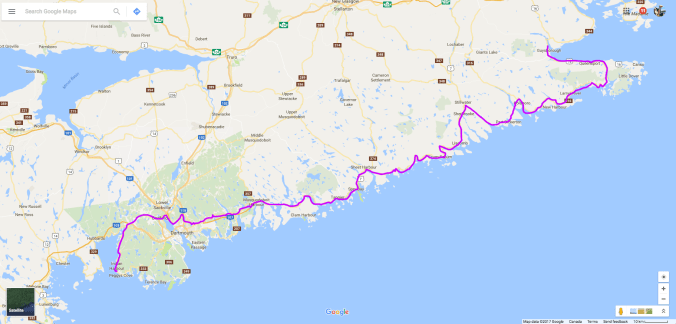

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

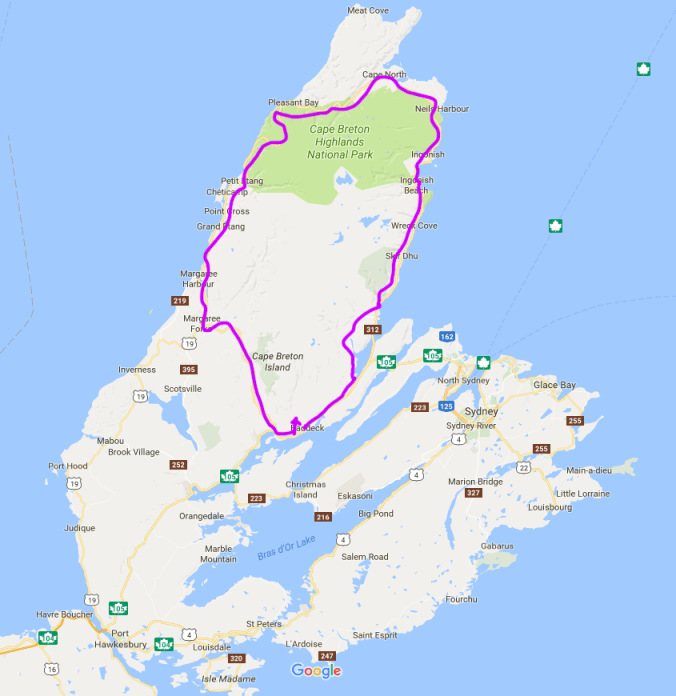

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.