In this final post in a series on gear, I discuss the navigation apps I use when touring.

“I learn by going where I have to go,” Theodore Roethke says in the refrain of his famous villanelle “The Waking.” That may be a good philosophy in life, but when motorcycle touring, it’s downright dangerous. There’s nothing worse than not knowing where you’re going and fumbling with a GPS in traffic while riding. Yeah, I’m all for exploration and adventure when you don’t have to be somewhere, but when the light is fading and you still don’t know where you are pitching camp, or when your fuel gauge is on one bar and you don’t know where the next gas station is, that’s a problem.

Charging

I learnt early in my touring experience that navigation is huge, maybe because I had so many problems keeping my phone charged. If the USB port detects moisture, the phone stops charging, and it doesn’t take long for a GPS app to drain your battery. And then there’s the cord. If your phone isn’t charging and the port isn’t wet, it’s probably the cord. They make them so cheap these days that the internal wires break. I once had to ride from the Cabot Trail over to the Best Buy in Sydney, NS, just to buy a new cord to get me home. What a pain!

So let me say at outset that if you don’t yet have wireless charging on your bike, you should. It’s a game changer. It avoids 90% of the issues you are going to face on tour. For years I worked around the charging problem by using the type of cord that has magnetic adapters. I siliconed the appropriate adapter into the port of my phone, then just attached the USB cord via the magnet to charge the battery. Rain didn’t affect the charging. The cord was still liable to break, but they are cheap and you can buy, like, a 4-pack on Amazon for $20 so can carry several.

The problem with this set-up is that the magnetic adapters are fine for charging, but most can’t transfer data, so now your phone is limited off the bike. Maybe you don’t want to silicone an adapter into your $1,100 iPhone 14. I worked around this by buying off eBay a cheap, used, military grade phone that I dedicated for bike navigation. It didn’t have a SIM card in it and was locked, but it didn’t matter: I used it in Flight Mode. That’s right, I don’t have a huge data plan and I ride in places that often don’t have cell service, so I download all my maps before leaving.

Navigation

The main app I use to navigate is OsmAnd+ because it is open source and includes free maps to be used offline. This is also great when I travel in The States because I don’t get hit with roaming charges. Last I looked, OsmAnd+ was about $20. I bought the Plus (paid) version because it imports GPX tracks, which I need for leading club rides, but the free version works perfectly well for navigation, if that’s all you need. OsmAnd also includes contour lines and hillshades layers. When I venture off-road, it’s nice to know how steep the mountain is going to be. There is also a Points of Interest (POI) layer so I can see gas stations, restaurants, healthcare, parking, and convenience stores and supermarkets on the map (configurable), and a Wikipedia layer, so I can see what significant landmarks I’m riding past or near. It’s a great little app, available for both Android and iOS.

I’ve tried maps.me, Gaia, Locus Map (Pro and Classic), Scenic, Eat Sleep Ride, and others, but I always come back to OsmAnd. It’s easy to use yet full-featured, a rare combination. It does what I need it to do and no more. Do I really need to know how far over I leaned the bike on my latest ride? Do I really need crash detection? Does my wife prefer to hear that I’ve crashed from an app or a person? But the main reason I like OsmAnd is for the free maps. I started using Locus Map Pro but maps are $1 per country. That sounds cheap—$1 for all of Canada—but for some reason they consider each state in the US a country, so that can add up fast. I still have these other apps on my phone as back-ups but I don’t really use them.

The other main app I use to navigate is Google Maps, now called just Maps. (I guess Google figures it’s so ubiquitous we no longer need the brand name.) Maps handles addresses better than any other app, thanks to Google’s AI. Need to know where a specific place is but you don’t know the address? Just Google it, then press the navigation arrow icon and it loads in Maps and guides you there. Easy peasy. As much as I like OsmAnd, you need a specific address for it to find your destination. (You can, however, press and hold on the map to choose a specific point of destination.)

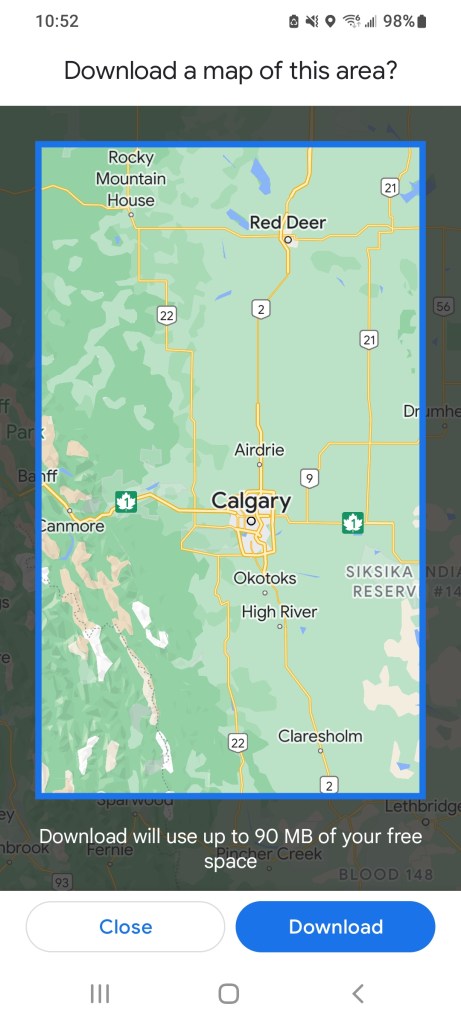

You can use Maps also offline, but like OsmAnd, you have to download offline maps before leaving home. (The search feature, however, does require cell service.) In the upper right hand corner, press your identity icon, then select Offline Maps from the menu. Press “Select Your Own Map,” zoom and position the frame using two fingers to select the area you want, then press Download. I name each map so I can keep track of them. They will expire if left unused for a certain amount of time, but you can update them all quickly and easily every once in a while when you are in a Wi-Fi zone. I downloaded maps for all the provinces I planned to tour before heading across the country. I didn’t need the northern part of most provinces, but I grabbed everything where I thought I might be riding. This was important since I was often not in a region with cell service.

The only other navigation app I use is Waze, and I only ever use it around town, frankly. That’s because it shows where the cops are. Nice! (Not that I ever speed.)

Route Planning

For route planning, I use the web-based Kurviger. Forget BaseCamp. Kurviger is intuitive and full-featured. I choose the type of route (highway, straight, curvy, very curvy; one-way or round trip), the origin and destination, and Kurviger comes up with an interesting route. I then drop in shaping and waypoints to shape the route exactly how I want it, flipping back and forth between Kurviger and Maps in street view to check the quality of the road. (Drag the little yellow man, ur, person, icon onto the map to see a street view.) When I’ve got the route exactly how I want it, I export it to a gpx file. Kurviger can generate a QR code for the file or hyperlink to share, or send it directly to Scenic, if that’s your preferred navigation app. I usually email the gpx file to myself then open it on my phone, which knows to open gpx files in OsmAnd.

I have Kurviger Pro on my phone as well, and it uses BRouter to do the routing. BRouter takes some setting up; like the offline maps in Googe Maps, you have to download in sections the areas you need first, but the upside is that you can use Kurviger Pro in the field. For example, say you’re riding with some friends and you’re looking for a good route to a specific place but nobody wants to pour over a map to make those decisions. Just open Kurviger Pro on your phone (it will load a map at your current location), press and hold on your destination, and it will generate a route—again, to the degree of curviness you want. You can even share the route with your friends.

Non-Navigation Apps

There are some other apps I use, not for navigation, strictly speaking, although they can be used for that. If you’ve followed Itchy Boots as she makes her way across the Americas, you will have heard of iOverlander. Noraly uses it to find her accommodations. I’m rarely sleeping with a roof over my head when I tour, but iOverlander is equally useful for finding campgrounds and even wild camping locations (i.e. places on crown land where you can camp for free). The app is user-based, and users submit descriptions and photos of the sites they’ve stayed at. This is helpful because there are a lot of people boondocking with campers and vans, and their needs are different than those who are tenting. So a safe gravel parking lot might be good if you have an RV, but not so nice if you are tenting. I wish iOverlander made this distinction, perhaps using a different symbol for each type of wild camping.

Last spring, a friend and I planned to camp at a state campground in Vermont, only when we got there it was closed. In fact, we were too early and all the state campgrounds were still closed for the off-season. (Doh!) So I opened iOverlander and it showed a wild camping spot a short distance away. We ended up at lovely site next to a river with a few other campers nearby for security and even a drop toilet to boot!

I also use weather and radar apps, of course, to monitor the weather. They are pretty straightforward so I won’t spend any time on them. But for the record, my preferred apps in this department are WeatherCAN and MyRadar. I like WeatherCAN because it’s generated by Environment Canada. I reluctantly open Weather Network only when I need a 14-day forecast, steeling myself for the clickbait.

The Best Riding App on my Phone

I’ve saved the best for last. There is one app that I have come to love, to love I say, so much so that it’s become almost indispensable. It’s an app like no other since it is an overlay on the Android system and replaces the usual interface. It’s called Drive Mode Dashboard, by Thork Racing.

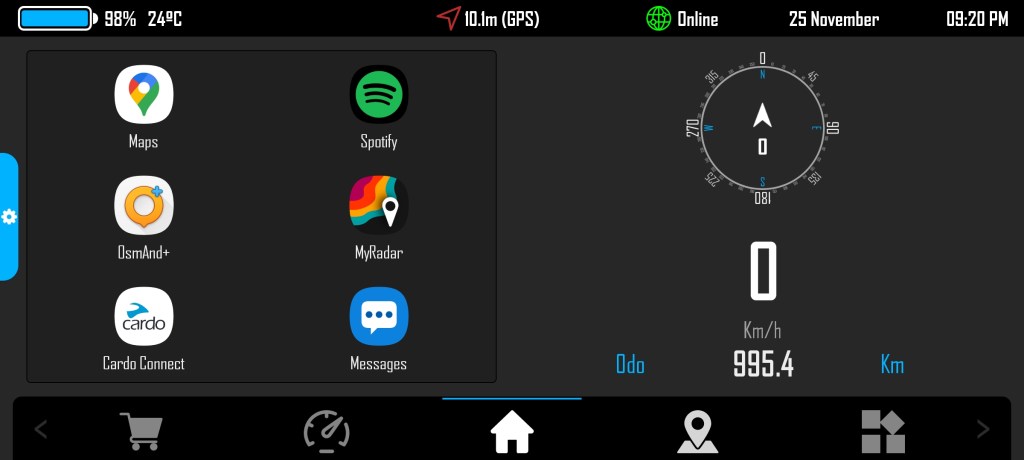

This is what I see when I launch DMD. (This is Version 2.0.) Instead of my usual desktop and app icons and widgets, I see this. It’s fully configurable but this is how I’ve set mine up—with a set of most-commonly-used apps on the left and a compass, digital speedometer, and odometer on the right. There’s more info along the top, as you can see. Along the bottom are icons for a map, my full list of apps, settings, even a digital rally book. Pretty cool.

But where this app really comes to life is in conjunction with Carpe Iter Controller, a bluetooth controller that mounts to my handlebar. With this controller and DMD, I can navigate throughout my phone—open any app, open and control media in Spotify, change the volume in my helmet, the brightness of my screen, and more. Where I use it most is to zoom in and out and pan around in maps. I think I could even tune my ECU while riding if I wanted to. About the only thing it can’t do is stop Microsoft Office Update from reminding me to check for updates every time I open Word! (Can Bill Gates avoid this?)

I see Thork Racing have a new unit out now with three buttons and a toggle and it can connect directly to 12V. My 1st generation controller has a rechargeable battery that lasts about a week with full-time use. There wasn’t room on the Beemer’s handlebar to mount it vertically so I made up a bracket and mounted it horizontally on the mirror stem. I have it mounted vertically on the Tiger, and yes, you configure the orientation in the driver software so the toggle switch pans your maps accordingly. Needless to say, with this set-up, if my eyes are not always on the road, at least my hands are on the handlebars. The controller is a little pricey but it’s a very nice modification.

Final Words

Despite finally getting my phone set up to be my primary means of navigation, I ended up buying a used Garmin Montana 600 for the big trip. I was nervous after having so many tours tainted by navigation issues and wanted a reliable back-up. The Montana has a WAAS-enabled GPS receiver and HotFix® satellite prediction. No, that’s not a dating service but the latest technology to ensure your connection to satellites is never dropped. The Rugged Mount is waterproof and robust enough for off-roading, and while I’m not positive, I think the Montana has a more comprehensive off-road mapping system than the phone apps. The Google Car made all the way up to Tuktoyaktuk, apparently, but it can’t go on single track or some of the ATV trails I do.

When all electronic devices fail, I rely on that thing called a paper map. No batteries needed! My Wolfman tank bag has a nice big clear plastic sleeve on top for them. It’s easy to lose sight of the big picture, so to speak, after staring into a 6″ x 3″ screen all day. I’ve recently discovered Butler maps, made for motorcyclists, and they are not only water resistant but also contain routes suggested by other motorcyclists and a ton of other information on the flip-side. I bought the one for The Maritimes and it currently hangs in my upstairs hallway outside my study, as did the one of North America I used to plan my cross-Canada trip. So a paper map serves multiple purposes: it’s great in the field, but it also serves to navigate me through the dark winter months of the off-season.

What are your preferred navigation apps and devices? Are there some I haven’t mentioned? Drop a comment below. I always like to hear from readers.