There are two ways to learn how to do something: trial and error, and getting some instruction. When it comes to motorcycling, I’m in for the latter. I’ve seen vids on YouTube of guys heading out onto the trails with their adventure bikes without any training. They seem to spend more time picking up their bikes and getting them unstuck from mud puddles than they do riding. It doesn’t look that fun. Then I stumbled upon Clinton Smout’s instructional videos and knew I would visit his school as soon as I got my licence.

Horseshoe Riding Adventures is located in Barrie, Ontario. I recognized the location from my teen years of skiing at Horseshoe Valley. Since I now live in Quebec (and start time is 8:30 a.m.), I decided to ride out the day before and camp nearby. I looked up the KOA in Barrie and gulped when I saw they want over $50 for the privilege of sleeping on a patch of their ground. Then I saw Heidi’s Campground at $18.50 and booked for the night before my class.

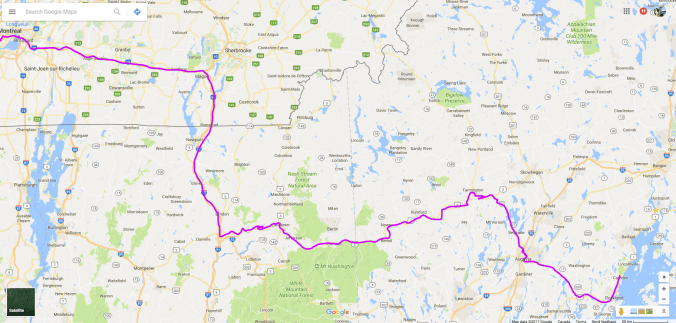

I was blessed with good weather and had a glorious ride out—once I got going. Two minutes into my ride I discovered a crack in my windscreen radiating from one of the mounting holes, the byproduct of a close encounter with some mud at the Dirt Daze Rally the previous month. I decided to turn around and fortify it with some super glue and add a rubber washer to allow some movement of the screen. This required a stop at the Rona in Vaudreuil for longer hardware. When I finally hit the highway I also hit the mandatory lane closure, this one at Coteau-du-Lac because, well, this is Quebec, and that’s the law! I lost another 45 minutes there and couldn’t get out of Quebec fast enough. My gas light was on for the final 40 kilometres before I limped into the MacEwan in Lancaster. (I knew I was cutting it close but had extra fuel on the back of the bike. I put 13.4 litres in the bike and the tank is 13.6, so I was close!)

Finally with these stresses behind me, I settled in for an amazing ride up Highway 34 from Lancaster to Alexandria, then west along the 43 which turns into Highway 7 and takes you all the way to the shores of Lake Simcoe, where I turned north up 12 and over the top of the lake. This ride took me through the farmland, scrubgrass, and vacation area of SE Ontario (in that order). I noticed that the driving gets more aggressive as you approach Toronto, with people forcing their way past a line of vehicles on a two-lane road, only to encounter the same people in beachwear and flip-flops at the next gas station. I was several hours behind schedule so kept my breaks short, arriving at Heidi’s just in time to pitch in the last of the light.

But all this is precursor to the raison-d’être of my trip: the full day class of dual-sport instruction. Since I’m on teachers’ summer schedule (groans please), I was able to visit the school on a Tuesday so had a smaller class than what I expect they have on Saturdays. I was in a group with two other people: Cheryl, who wanted to get more comfortable on her 800GS, and Bruno, who rides a Harley but felt he needed a little something extra; yes, dirt riding makes you a better and safer rider on the road too. Our instructor for the morning was Graham, one of Clinton’s sons and who, by virtue of his good genes, had the best summer job of any of his classmates, I’m sure. We would be on Yamaha 230s for the morning part of the class. He had us start by just riding a few laps of a course laid out in what staff refer to as “the pit.” It’s a large, open area of dirt and some sand with a few jumps, surrounded by a grassy hill with trails cut into the bank to practice hill climbs. After assessing our abilities and needs, Graham started with the instruction.

I had a burning question going into this day, one that stemmed from my experience at Dirt Daze, and Graham provided the answer early on. While riding the back roads of New York, I’d experienced the front end sometimes slide out while peg-weighting and wondered how you prevent that. Graham demonstrated that you actually hold the bike up with your thigh while counterbalancing. So if you want to turn right, yes, you weight the right peg—I knew that much—but you lean your body to the left (as the bike tips to the right) and prevent the bike from low-siding by pressing your inner right thigh into the tank. Later during a water break, Clinton came by and suggested we try standing pigeon-toed on the pegs; this position presses the thighs into the tank and stabilizes the bike. But where YouTube, reading books, and listening to instruction is helpful, the real learning happens when you get to practice specific skills in a controlled and relatively safe environment. The little dirt bikes allowed us to try things without all the weight (and potential expense!) of our own bikes to deal with. We did some slalom in the dirt, some hill climbs, and different types of descents. Then the real fun started: we headed out onto the trails.

There’s little that I’ve experienced that’s more fun than riding a dirt bike on forested trails. I won’t make comparisons with sex, flying, writing poetry, scoring, or music—my other passions—because such comparisons would be impolite to some and unfair to others. But it’s really, really, (really) fun, and that’s before you get to the mud ruts. I went down in the mud a few times at Dirt Daze so was under-confident and nervous about riding in the mud. Horseshoe Adventures provided some “deep-end” opportunity to get over this fear quickly, again, in a controlled environment, on a smaller bike, and with the guidance of an instructor. We were given three options for getting through a huge mud rut. One was to paddle with our boots on either side as we ride through the rut; the other was to ride seated but feet up, and the third was standing. I was going to do the easiest, but once into the rut I felt comfortable enough to ride it out and didn’t paddle. The second time through I stood and made it through without dabbing! Okay, it was better than sex, maybe like sex in a mud puddle while watching the World Cup and listening to Sex Pistols.

Graham also had us practice tight turns, throttle control, log crossings, and some pretty big hill climbs and descents in both rocks and sand. This is where the practice in the pit really helped and I could see the application of skills learned there in the real world of trail-riding. After a full morning, it was time for lunch.

In the afternoon, I headed out with a new instructor, Emily, on my own bike. I was a bit nervous because of my 85/15 tires, but was assured they’d be okay for what we were doing. A few times around the course and I immediately began to see how the skills I’d learned in the morning on the dirt bike were applicable to my 650GS; it’s just more weight to manage. Emily took me to another network of trails and we began bombing through them on our dual-sports (she was on an 800GS), that is, until I misjudged a turn, drew on asphalt muscle memory, hit the front brake, then the dirt! Umph! Lesson number one: you can get away with that shit on a 230 dirt bike with knobbie tires, but not an a 650 with street tires. The next lesson, then, was emergency braking in the dirt. We went to a dirt road and Emily had me lock up the back brake, getting used to the back end fish-tailing; then she added a little front brake. Her first question to me when I’d picked myself up off the dirt after my fall (after “Are you okay?”) was “How many fingers did you have on the brake lever?” I couldn’t remember but probably all of them except the thumb. A hand-full. Two fingers only, she advised. Graham had said the same about the clutch hand in the morning.

We also did some rocky descents, 2nd gear, a little front brake. Then back to the trails where I found my redemption when Emily took me through the same infamous corner that had bested me before. We also did some pretty big whoops at speed, some of them muddy, and some more climbs and descents but this time on the trails, not the road; each context changes the skill slightly. It’s like how they say a dog has only learned a command if it can reproduce the desired behaviour in five different contexts. This was made more evident in my next exercise, which was throttle control, doing figure eights in a small grassy area with uneven terrain. I’d practiced this fairly successfully in the gravel parking lot back at the pit, but doing it on uneven ground with a slight grade made me realize I’m more confident with my right turns than my left. I needed to reproduce the body position I felt comfortable doing on my rights—hanging out with my right calf against the bike holding me up—but with my left. Emily also spotted that I needed to twist my body more; small, subtle changes made all the difference, and soon I was turning both ways full lock.

Back at the pit, my final exercise was recovering from an unsuccessful hill climb. This is a skill for when you’re partway up and realize you’re just not going to make it and want to bail. You use the back brake, stall the bike, but let the clutch out and the engine will hold the bike. Then you turn the handlebars, feather the clutch to let the bike roll back in an arc until it’s perpendicular to the hill, all the while leaning the bike uphill and keeping your uphill foot down. Then rock the handlebars back and forth until the bike is positioned where you can safely pull in the clutch and roll down the hill. You can see Clinton demonstrate it here. Emily showed me how it’s done and it looked so easy-peasy I was overconfident when trying it. It’s actually a lot harder than it looks! You have to keep concentrating the whole time because if you lose your balance and want to plant that downhill foot, you’re in trouble. That’s what I did, and then muscle memory kicked in and I did what I always do when riding and get into trouble: I pulled in the clutch. Doh! Next thing I knew the bike was on its side and I was on my back. We couldn’t rotate the bike because the crash bar had dug in, so we grunted it up, and I finished the manoeuvre. Then I tried it again, and a third time, until I was confident I could do it when needed in the field.

My experience at Horseshoe Adventures was everything I’d hoped it would be and more. As it turned out, Emily is from Cape Breton, where I plan to tour next week, and she gave me some recommendations on restaurants and trails. There’s one called Highland Drive (of course) that traverses Cape Breton from Wreck Cove to Chéticamp, and another from Meat Cove, where I plan to spend a night. Of course I’ll do The Cabot Trail with the Harley boys, but then I’ll cut back through the bush and do it all again. I have a bike that is not restricted to pavement but my skills were holding me up. Now I feel I have the skills to ride these roads safely, which is exactly why I went to Clinton’s school.

I can’t praise the instructors at S.M.A.R.T. riding adventures enough. At lunch, Clinton and I got talking pedagogy, and he said they spend a lot of time choosing and training their instructors. It’s evident. Yet what makes this place special is not just the level of instruction and professionalism of staff but how you immediately feel like family. That sounds cheesy, I know, but there’s definitely a personal touch to this school. Clinton is always around, flitting in and out, asking how the day went and making sure all his clients are happy.

With my bike re-loaded and my head filled with new skills, I headed off toward Guelph, where I planned to spend a few days with my parents. There’s some beautiful geography between Barrie and Guelph, and my GPS took me through Creemore, Orangeville, and Fergus along county roads. Halfway towards Guelph, with the sun low and glowing across the farmers’ fields and massive wind turbines rotating in slow motion, I realized I was riding with two fingers on the clutch, two fingers on the brake.