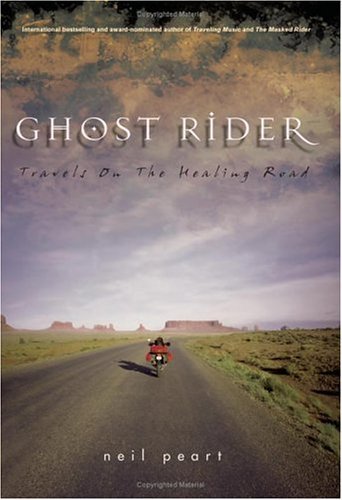

The riding season is coming to a close here in Montreal and I’m already thinking of what I’ll read in the off-season. When you can’t ride for five months of the year, you need to have a few motorcycle-related books ready to carry you through those dark winter months. Last winter, two such books for me were Neil Peart’s Ghost Rider (2002, ecw press) and Ted Bishop’s Riding With Rilke (2005, Penguin).

I first came across Peart’s Ghost Rider while visiting the excellent Bookshelf Cafe in Guelph, Ontario, many years ago when the book was first published. It was on the display shelves just inside the door and I remember picking it up and never getting much deeper into the store. As a drummer, I knew of Peart. In fact, he was the hero of pretty much every snare drummer of the marching band I was in through my teens. He apparently even started drumming in a drum corps not far from Burlington, my home town, so it was almost like we were best buddies. We would air-drum to Moving Pictures at the back of the tour bus, pretending we actually knew how to do Swiss Army triplets on double bass drums or half the other stuff he does. But then that’s the advantage of air-drumming: no one can hear your mistakes.

I’d heard of the tragic loss of Peart’s daughter and wife, and of his decision to hit the road in search of a reason to continue living. All this was long before I started to ride, but the dream of riding and touring one day was alive and well, so the book grabbed me and held me there for some time. Eventually I began to imagine the staff thinking “Either sh*t or get off the pot!”

It is a compelling story. His daughter is killed in a single car accident en route to Toronto for first-year university; eight months later his wife is diagnosed with terminal cancer, an illness which he more accurately describes as “a broken heart.” Soon after, he finds himself alone and slipping deeper into isolationism and self-medication. The only way out, he decides, is literally to flee, not knowing exactly to where or why. Like the survival strategy at the heart of Peter Behrens’s The Law of Dreams, a book also about tragedy and loss, Peart intuitively decides “to keep moving.” All this is provided in the opening chapter and sets up the “travels on the healing road” westward on his BMW R1100GS.

We follow Peart across Canada, up into Inuvik, across to Alaska, then down into The United States to Las Vegas (which he hates) and around the southwest. But the travels are really just the subtext to the real “journey” (to use the most over-used word today) for him on the road of grief and recovery. Peart provides a strikingly candid view into his emotional life at its core. He is extremely self-aware and offers us insights into how he was able to inch his way out of the dark pit into which he’d fallen: his fears, his strategies, his discoveries, his small advances and set-backs (he describes the process as one step forward, one step back . . . minus an inch).

The motorcycle is the key element in his recovery. It provides a distraction from the thoughts and feelings that plague him; riding is so consuming, it’s difficult to think of anything else but operating the vehicle while you’re on it. And he puts on the miles. (Section headings include dates, places, and mileage.) The bike also reawakens his senses which have been numbed by grief and intoxicants. One of the first signs of recovery occurs while riding twisties through the B.C. interior on Highway 99, “one of the great motorcycle roads in the world”:

The sky remained bright, the air cool and delicious, and the sinuous road coming toward me was so challenging and rewarding that I was tempted into the adrenaline zone. Turn by turn my pace increased until I was riding with a complete focus spiced by the ever-present danger and occasional thrill of fear, racing against physics and my own sense of caution in a sublime rhythm of shifting, braking, leaning deep into the tight corners, then accelerating out again and again. I felt a charge of excitement I hadn’t known for many months and found myself whooping out loud with the sheer existential thrill.

Another important element in his healing process is journalling. In one late-night entry, for example, he stumbles upon a subtle but important discovery—forgiveness—the need to forgive life for doing this to him, forgive others for being alive, even to forgive himself for remaining alive. And when he’s not journalling, he writes letters—yes, long-hand—to friends and confidantes, setting his thoughts and feelings onto paper where he can see them. Sections of the book are these letters printed verbatim.

Peart provides commentary on the people he meets and the places he visits. He prefers the peace of rural roads to the hustle and bustle of urban centres, not surprising for a man who is comfortable with solitude. He finds healing properties in nature, especially birding. Peart clearly considers himself a cultured man and does not suffer the uncultured easily. At times, he seems downright judgmental and misanthropic. This was perhaps the most surprising aspect of the book for me. But I guess he applies the same honesty in describing his thoughts of others as he does about himself. When he describes a friend of his as possessing “a blistering contempt for most of humanity,” I cannot help thinking he’s describing a part of himself as well. The next sentence begins, “We agreed on many things . . .”

I’ve fortunately never suffered such loss, but I found his examination of grief and grieving fascinating. I do feel that some of that material could have been condensed. The book is over 450 pages in length with, like I said, entire letters reproduced for long stretches of the book. I feel the book needed more editing, or better editing, with Peart forced to distill for us the musings in those letters down to the essential discoveries. No doubt this was a structural decision made by Peart and his editors, but I feel he took the easy way out. There’s also an awful lot in this book that simply isn’t that interesting. Do I really need or want to know what he eats at each meal, his wine choices, the birds he spots, the flora and fauna along the way? His encounter with a short-eared owl is an example of a meaningful reference to nature because it’s linked to the main theme of the book (i.e. the owl shrieks a cryptic message at him) but other references seem gratuitous.

Yet ironically, the end comes upon us rather suddenly and the book overall feels truncated. We learn in the final chapter of finding new love that is the final step in his recovery, if there ever can be a final step, and it comes in a matter of a few sentences literally a few pages from the end. Overall, I get the sense that this book was rushed to press by a deadline. It’s a good book, but it could have been a great book with more time and effort in that crucial revision and editing stage. Now I’m sounding like a teacher leaving feedback on a student paper, so I’ll move on.

Like Peart’s Ghost Rider, Ted Bishop’s Riding With Rilke (finalist for the Governor General’s Award for nonfiction, among other nominations and awards) opens with a tragedy: Bishop’s life-threatening crash. He’s riding his partner’s classic BMW and is encountering some high-speed wobble each time he creeps up to 130 km/hr.. Then he tries to pass a semi, only to find out halfway past it’s a double-semi, a van rounds the corner in front of him and . . . well, it doesn’t end well. Like Peart’s opening, this serves as a frame narrative for the musings that follow. And also like Ghost Rider, Bishop weaves two threads through his text, or two passions: motorcycles and literature.

Bishop is an English professor at The University of Alberta with a specialization in early modernism. Much of the book describes a ride down to the University of Texas in Austin to do research on Joyce, or is it Virginia Woolf? I’m not quite sure. The narrative jumps around quite a bit between different Special Collections rooms in several libraries and his office at U of A to conferences, but it doesn’t really matter since the academic work is just the pretext to the musings on literature and adventures on the road. Along the way we get anecdotes about D. H. Lawrence in Taos, Camus wanting to buy a motorcycle, the Woolfs declining to publish Ulysses, Ezra Pound as Bishop passes through Hailey, Idaho, Pound’s home town, and some lowbrow culture too, including Evil Kneivel’s attempt to jump the canyon. (Remember that one? It’s still an embarrassment to the locals there.)

I had come across Bishop’s writing earlier in Ian Brown’s What I Meant To Say. His essay “Just a Touch” is my favourite of that collection, so I was excited when I received this book as a gift from a writer friend. My expectations were happily fulfilled. Where Peart’s prose is often a bit wooden, Bishop’s is graceful, imaginative, and often funny. Here he provides one of the best descriptions of riding I’ve seen:

When I first put on a full-face helmet, I have a moment of claustrophobia. I can hear only my own breathing and I feel like one of those old-time deep-sea divers. . . . . When you hit the starter, your breath merges with the sound of the bike, and once you’re on the highway, the sound moves behind you, becoming a dull roar that merges with the wind noise, finally disappearing from consciousness altogether.

Even if you ride without a helmet, you ride in a cocoon of white noise. You get smells from the roadside, and you feel the coolness in the dips and the heat off a rock face, but you don’t get sound. On a bike, you feel both exposed and insulated. Try putting in earplugs: the world changes, you feel like a spacewalker. What I like best about motorcycle touring is that even if you have companions you can’t talk to them until the rest stop, when you’ll compare highlights of the ride. You may be right beside them, but you’re alone. It is an inward experience. Like reading.

In another section, Bishop’s sense of humour mixes with a cutting derision toward literary pretension, producing a description of an open-mic event in Taos that would make Peart giggle in sympathy:

Next up was Ron, the leather-jacketed poet from this afternoon. When his name was called he left the room and then came slouching in from the street wearing shades and sucking on a cigarette and carrying a little cassette recorder playing Thelonious Monk. This might have been cool, except that the efficient MC, thinking his poet had gone home, had already started making announcements about next week’s reading. So Ron had to stop, turn off the recorder, and go back outside. His friends cried, “No he’s here, he’s here!” The MC stopped, and Ron slouched in again with the same Thelonious Monk riff playing. He shouldered his way through the group of three in the inner doorway, snapped off the cassette, whipped off his glasses (briefly snagging one ear), and looked up from his crumpled exercise book. “Why do I love you!?” he shouted.

Who cares!? I wanted to shout back, but I was a well-bred Canadian and this was not my town. Knowing this could only get worse, I slid out into the night. I understood now what Lawrence had feared in Taos.

What I especially enjoyed about Bishop’s writing is his ability to render scenes like this so vividly. I’ve been at poetry readings like this—heck, I might have participated in some—and they are as painful as he describes here. He had me squirming. His attention to descriptive detail (the slouching, the snagged sunglasses) and use of dialogue (the shouts of Ron’s friends)—fictional techniques—allow us to stand next to him, so to speak, at that poetry reading. No wonder he teaches a course on creative nonfiction and has received numerous awards and accolades for his travel writing.

In addition to the places he visits, Bishop also takes us into his world of academia. We sit in on his meetings with the department Chair, overhear the casual conversations at academic conferences, and look over his shoulder in the British Library’s Manuscript Room as he discovers he’s holding Virginia Woolf’s suicide note. We even lie beside him in the ditch as the emergency responders cut off his boots and jacket, and next to him in the hospital bed as he takes his first drink. (Okay, we’ll drop this line of thought now.) This is what good travel writing does: take us to places from the comfort of our reading chair.

And always at the centre of Bishop’s writing is an affable man with a sense of humour, important qualities in a travelling companion. We get the sense that Bishop would be a great guy to share a beer with and chat about literature, or bikes, or both, which is what Riding With Rilke is. In fact, I’d like to share a beer with either author, although with Peart it would more likely be a wee dram.

I enjoyed both books. When I went to Amazon to search for more like them, I discovered a whole genre I hadn’t known existed: motorcycle journalism. From Hunter S. Thompson to Che Guevara, Persig, and Ewan McGregor (one of these things is not like the other) there are now many good books about the personal experience of touring by bike as the adventure riding industry continues to grow. With my 6a licence now finally in my wallet, I only have one more winter to wait before I can hit the road myself and hopefully add my voice to the motorcycle travelogue market.