The term “adventure” is so over-used today that it’s lost almost all meaning, but this is how I define it.

In a recent episode of Adventure Rider Radio RAW, host Jim Martin and guests tried to define the word “adventure.” It was a rather abstract discussion that quickly deteriorated into subjectivity and personal perspective, yet the poet and wordsmith in me was piqued. Since I use the term in my blog’s byline and hold the expression “life is an adventure” as a personal motto, I thought I should take a crack at defining it. Yes, the term means different things to different people, but here are the elements of adventure riding as I see it.

Exploration and Discovery

There has to be an element of exploration and discovery. Adventure riding is going where you’ve never gone before. I suppose in this sense, all travel has an element of adventure, as it gets us out of our milieus. One of my favourite things is seeing something for the first time, and like the proverbial first step into the stream, we can only see something the first time once; it’s never quite the same again.

I’m a curious person, whether in the realm of ideas or things. Adventure riding allows me to follow that curiosity, leading me into the unknown. There’s a mystery at every geolocation in the world and all we have to do to solve it is go there and look. That’s why it’s important to go slow and stop when something catches your eye, because there’s no point on going somewhere if you aren’t looking.

Sometimes what there is to see is geography, sometimes people, sometimes architecture, art, or any number of things, and sometimes it’s an unknown aspect of ourselves.

Challenge and Risk

At one point in the podcast, Jim Martin tries defining the term by finding something that it is not. (This is called Definition by Exclusion, i.e. A is not B.) He uses as his example the quintessential insult of every adventure rider—a trip to the local Starbucks. Surely a ride to Starbucks and back is not an adventure, he posits. But one of the guests argues that for someone suffering from social anxiety, maybe a trip to Starbucks is an adventure.

What this line of thinking suggests is that personal challenge or risk, even perceived risk or fear, is one element of adventure. We are moving out of our comfort zones, however large or small, where personal growth occurs. We are moving, as Jordan Peterson would say, from order into chaos.

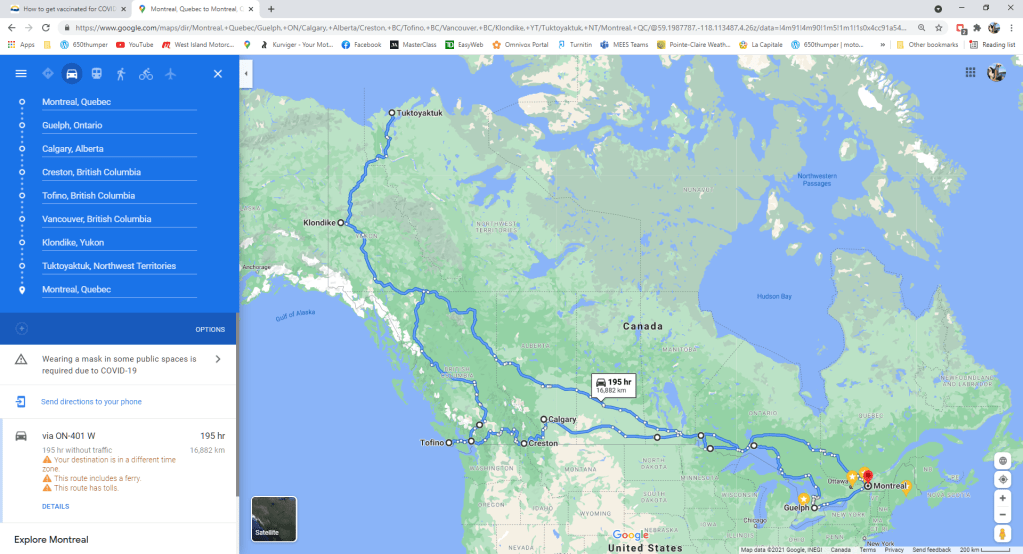

I’ve written before about the thrill-seeking aspect of adventure riding, those people who seek danger by riding extremely remote roads like the Trans-Taiga, or dangerous parts of Mexico and South America. On this topic, I like what guest Michelle Lamphere said: the experience has to be meaningful. Risk for risk’s sake is merely being foolhardy, but risk in order to have a transformative experience is another element of adventure as I define it. That’s why I’ll probably never do the Trans-Taiga but surely will go back up The Dempster and complete my ride to Tuktoyaktuk. (I was prevented entry to NWT because of Covid restrictions.) The former is a lot of mind-numbing forest leading to a dam, but the latter is some of the most astounding geography I have ever been privileged to witness.

Risk in itself is not an adventure, but risk is often part of adventure because we need to risk in order to discover.

Off Road, En Route

I don’t think you have to go off road to have an adventure but it sure helps. That’s because when we go off road, we get away from the conceptual order of civilization. Canadian nature poet Don McKay refers to this geographical and epistemological space as “home,” and “wilderness,” by contrast, as “not just a set of endangered spaces, but the capacity of all things to elude the mind’s appropriations” (Vis à Vis 21). When we ride off road, we move from the realm of human to other. As the road deteriorates from asphalt to gravel, then dirt, trail, and bush, we shed the trappings of our everyday lives, where deep discovery can happen.

In Classical Literature, this journey is called Katabasis, the motif in which the hero descends into the underworld in search of valuable, hidden knowledge. Aeneas in The Aeneid does it, as does Odysseus in The Odyssey and Dante in The Inferno; they each make the dark journey through Hades in the hope of finding enlightenment. For Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, the route to personal growth involved a similar descent into what he called The Shadow, the unconscious.

I don’t think it’s coincidental that the archetypal symbol of the unconscious in literature across cultures is wilderness—the forest, the jungle, the sea—untamed geography untouched by human power. When we ride off road, we are riding figuratively into the unconscious. Guided by our GPSs and with the support of our satellite trackers, we face adversity in its most primordial form, and what we hope to find, somewhere at the nadir of this adventure, is a mental and physical toughness we never knew we had.

Spontaneity and the Unplanned

Do you make reservations ahead of time when you’re touring, or do you wait until mid-afternoon, then start looking for accommodations? I generally like to wait so I’m not committed to being somewhere by a certain time. It allows me flexibility so I can follow my nose and explore where it leads. Similarly, I often don’t have a set route. I have a general destination, but how I get there is a matter of choice. See an interesting dirt road—why not check it out? Once while riding along the Sunrise Trail in Nova Scotia, I noticed some 2-track leading off from the road toward Northumberland Strait. My curiosity got the better of me and so I followed it to a picnic table on the edge of the cliffs looking out over the water—a perfect lunch spot.

For this reason, I also often tour solo, although lately my feelings around that are changing. Riding solo of course provides you with complete autonomy to determine the route, the pace, the accommodations, even what attractions to see. The downside, however, is that you have to be more conservative in what risks you take. This past summer I had the opportunity to ride through a ZEC, which is a nature reserve here in Quebec. I was at the gate paying the entry fee when the staff person mumbled something about “trois cents.” What now?! Three hundred kilometres of off-roading solo with no one around? He actually advised against it. There are a lot of moose in there, he said. So I changed my planned route. As I age, I’m less inclined to take risks. The best of both worlds is to find a riding partner or partners who are compatible in riding skills, personality, and philosophy.

If your route, your accommodations, your attractions are all determined before leaving home, if your entire trip is scheduled, you aren’t really on an adventure; you’re touring. That’s fine, if that’s what you’re into, but allowing something unexpected or unplanned to happen, again, provides greater opportunity for discovery. Perhaps what is essential in this aspect of adventure is that we relinquish control and, instead of acting upon the world, we allow something to happen to us.

An ADV Bike

This one is probably going to be the most controversial. Do you need to have an ADV bike to have an adventure? No. Certainly not. There are people riding around the world on postie bikes, 50cc mopeds, and at the other end of the scale, Gold Wings and Harley cruisers. But I’m going to ask the question, why? My dad always said use the right tool for the job, and I question whether these machines are the best choice. While it’s not a requirement, having an ADV bike will allow you to have an adventure a lot easier than on another machine. Here are the key elements of an ADV bike, IMHO.

It has to be off-road capable. That means good ground clearance and knobby tires. Missing one or the other is seriously going to limit where you can go.

It has to be comfortable, with a large seat (not a dirt bike seat), a windscreen and faring, and good ergonomics. ADV riding is not about crunching the miles, but having a bike that can do it gives you the option if needed. You’re going to be spending the entire day on the bike, so it must be comfortable.

It has to be light enough to pick up on your own. It’s ironic that the big GS, at 600 lbs., has become the iconic ADV bike. Can you lift this bike and gear on your own should you drop it in the middle of nowhere? Okay, it carries its weight low and can be lifted with the right technique, but do you need all that power? I think the ideal ADV bike is a middle-weight at 650-900cc, maybe even smaller—big enough to crunch the miles comfortably, but small enough to lift on your own.

It has to be reliable or fixable. One of the reasons the Ténéré 700 is so popular is that it has minimal tech and one of the most reliable engines in the industry. You also have to be able to source parts from remote places when there is a problem.

It should be able to carry some luggage. The adventure rider is going into remote areas so has to be self-sufficient. That means carrying tools and tubes, some spare parts, clothing, maybe a tent and cooking equipment. Itchy Boots has travelled extensively without driving a single tent stake, but carrying camping and cooking gear frees you from the burden of having to find shelter when the sun goes down.

What’s in a word?

No doubt I’ve pissed off a lot of readers with this post, but I’m open to alternate viewpoints. Yes, words and the phenomena they refer to are somewhat subjective, but if we’re trying to define a term, we have to be somewhat exclusive or the word loses precise meaning. When words get over-used, they tend to lose that quality, so this is my attempt to rescue the term “adventure” from marketing and corporate interests.

What would you add or subtract from my definition? Leave a comment below. I’m not an ADV snob, but I am rather careful with words. I agree with Flaubert that one must strive to find le mot juste (the right word), but that begins with having the word right.

In the end, even this poet will acknowledge the limits to language. Words are crude signs we use to point to phenomena but never perfectly convey their meaning, and definitions of words are yet another semantic step away from the actual thing. However, if you get yourself an adventure bike and head out with no definite route but guided by curiosity, pushing through fear into the unknown, you will discover that the word “adventure” means much more than the sum of its parts. It’s the closest thing I’ve found to complete freedom, something even resembling joy, but then these too are only words.

It climbs as it heads north, opening up into farmland and views of the distant mountains.

It climbs as it heads north, opening up into farmland and views of the distant mountains.