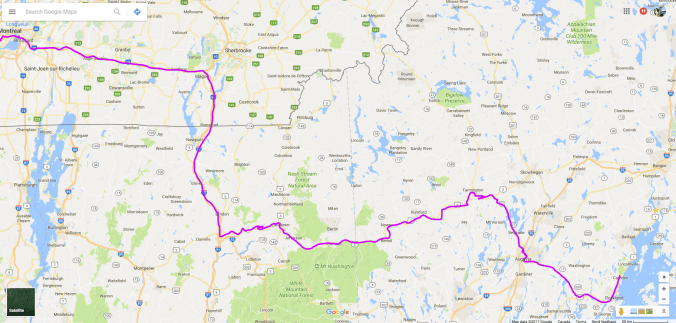

Imagine the perfect motorcycling road. What would it look like? It would have lots of twisties, of course, and probably some hills too. Curving hills, climbs and descents, to make it extra challenging. It might even have some switchbacks. And for scenery, it might have mountains, or some water, like an ocean. Well, the Cabot Trail has all of these, which is why it’s on every rider’s bucket list. 360 kilometres of climbing, snaking twisties with mountains on one side and spectacular ocean views on the other. It was my destination for this trip and worth every one of the 1,739 kilometres it took to get there.

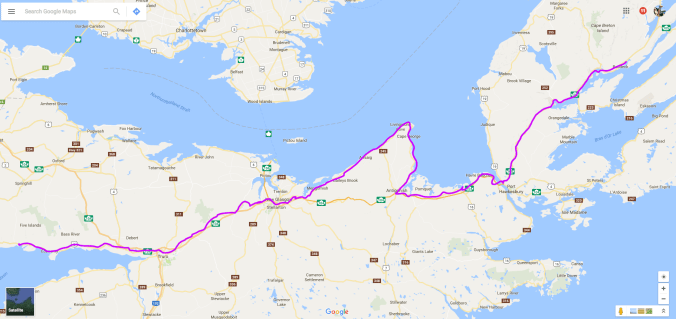

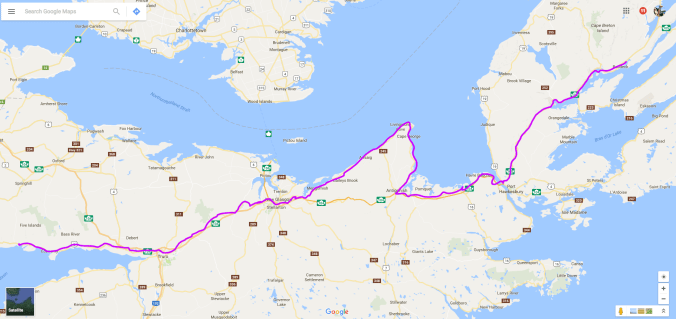

But I didn’t want to put all my eggs into one bucket, so to speak, so getting to the Cabot Trail was part of the fun. I left Deer Island at Lord’s Cove on the free ferry run by the New Brunswick provincial government and landed in L’Etete, NB. From there, I bombed through the drive-through province on the Transcanada and into Nova Scotia. I’d been reading Alistair MacLeod’s Island to get a sense of Cape Breton culture, and since almost every story has some reference to mining in it, I thought I should visit a mine. So my first stop in Nova Scotia was at Springhill, about 20 minutes past the border.

Springhill. The name is synonymous with disaster. There have been three major accidents at the mine: an explosion in 1891, another in 1956, and a bump in 1958. A bump is an earthquake that causes not the roofs of tunnels to collapse but the floors to rise up to the roofs. It results in overturned railway cars and crushed or trapped men. 75 men died in that last accident; 99 were rescued, including some who managed to stay alive for 8 1/2 days by drinking their urine before a rescue team broke through. The mine is now a museum; you can walk 400 feet into the shaft on a guided tour.

I found the tour moving, the place solemn, even sacred, and I didn’t take any photographs while underground; it just didn’t seem like something I ought to do. Besides, in this instance, a photo does not come close to reproducing the feeling of being down there. If you’re interested, there is always Wikipedia, which covers the three disasters well, with photos of the mine.

In a regular 8 1/2 hour shift, each miner had to extract and load 10 tonnes of coal. The coal is extracted largely by hand, with hand tools like a manual auger. The miner would press a steel plate strapped onto his sternum against the butt of the auger and turn, boring into the wall of stone in front of him. I’ve used a power auger to dig down into earth, and it’s hard enough, even with the advantage of leaning your weight into a softer substance. But to have to press into a wall of stone in front of you and turn by hand is almost unimaginable, and to do that for 8 1/2 hours is inhuman. Each miner has a lunch bucket and flask of water, both steel to prevent rats from eating the lunch, although they would still chew through the cork, dip their tail into the neck of the water jug, and get water that way. (Obviously no concern about double-dipping for them.) Despite these threats, the rats were appreciated by the men, and in fact were helpful in warning of disaster. On the day of the bump, the rats vacated the mine. Many of the experienced miners did not show up for work that day, but many younger ones did.

Given these working conditions, it’s not surprising that the first legalized trade union in Canada was formed in Springhill. I did take photos of the memorial in the centre of town, and a plaque commemorating the surreptitious meeting that established the union.

Those four tall memorials behind contain the names of “others who have lost their lives in individual accidents.” So while so much attention is placed on the three disasters, there were hundreds of other men who died in single incidents during a workday. Many men lost their lives from runaway railway cars; you’d have to jump out of the way or be crushed, and it was extremely dark down there. In fact, the guide turned out the lights for a few moments and it was unnerving. To be trapped down there in the dark would be horrific. He also showed the actual lighting conditions of the miners (the museum had added extra lighting for tourists), pre- and post-20th Century. Pre-century lighting was so poor you basically could only see the small section of wall in front of you on which you were working, nothing more. I’m glad I did this tour; it’s ironic that the most surprising and memorable moment of my trip was off the bike, down in that mine.

After that experience, the sensation of being on the bike was all the more liberating. Up in the sunshine, I sped to my next destination, which was 5 Islands RV and Campground. I say sped but, thanks to Googlemaps, which does not discern between a dirt or paved road, 16 kilometres of Highway 2 taking me there was gravel. But the view, once there, was worth every one of them.

If you look closely at the people beside me (in the centre of the photo), you’ll see a motorcycle parked behind that boat. I struck up a conversation with these nice people, a young couple travelling with their son. They live the other side of the bay, directly across that body of water, and told me of a nice route to get to Cape Breton. You go into Truro, then head to Bible Hill, where you can pick up Highway 4 (aka Old Highway 4) which snakes back and forth across the Transcanada Highway and is a lovely ride! I split off at the 245 instead of going through Antigonish and rode a section of the Sunrise Trail up to Cape George.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

Like I said, with motorcycling, it’s not the destination but getting there that is the fun. But finally, I did cross the causeway and found my way to Baddeck Cabot Trail Campgound.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

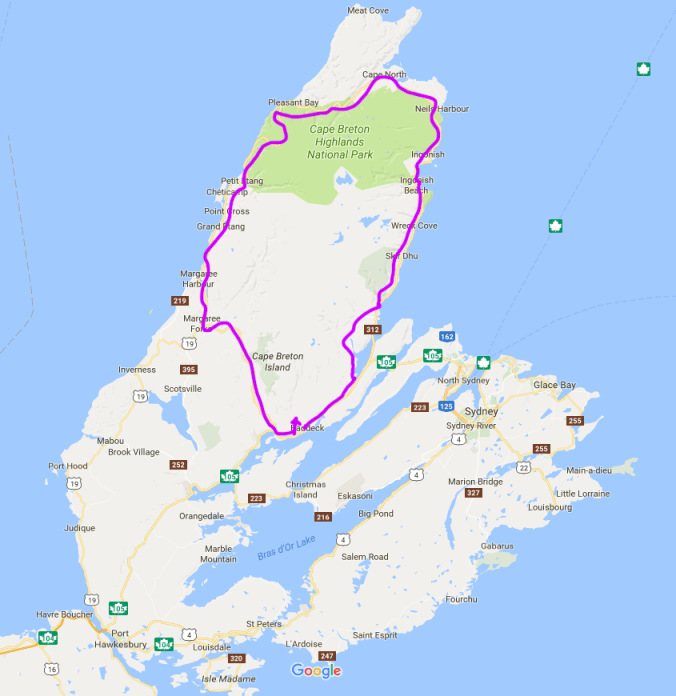

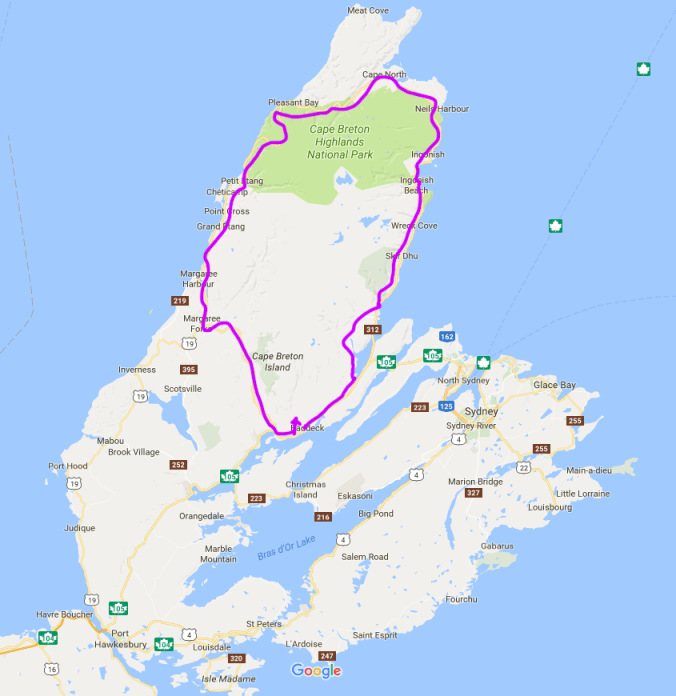

The next day was it, the Cabot Trail. Now whether to ride it clockwise or counter-clockwise is a matter of some online debate, but to me it’s a no-brainer: doing it counter-clockwise means you have the ocean views, and hence the lookouts, on your right side. Doing it the other way would involve crossing traffic every time you want to pull off or continue. And there are some spectacular lookouts you don’t want to miss.

But I have to admit, I didn’t stop at many. To me, they seemed like a distraction to why I had come all that way, and stopping every 15 minutes would prevent me from finding a rhythm on the road. So I rode. Yes, it’s only 360 kilometres and will take you only an afternoon, but it’s pretty intense riding, requiring your full concentration if you are, like me, not interested in cruising. For me, part of the fun is challenging myself to really ride a road properly—not dangerously, I always leave 20% buffer—but on a piece of road like this, you don’t want to be poking along like on a Sunday drive. So yes, that involved some passing too on this two-lane road.

It’s a clinic in riding, and by the end of the day I felt a lot more adept at cornering and passing. Do any repetitive skill for a day and you will get it down. I remember learning to canoe properly. One day in the stern and you learn the J-stroke and the Power-stroke. One day in the bow and you are a pretty good navigator of nautical maps. The same for riding. Now I know why it’s so important to fully brake before a sharp turn. If you go into it at the speed you think you can take it, you don’t have any buffer should you have misjudged. But by braking into a corner, you can determine your speed through the turn using the throttle, not the brake, which might have disastrous consequences. And by accelerating through the turn, the torque of the bike is pressing the rear tire into the road, increasing traction and preventing lowsides.

I also discovered that my little pony really pulls! There were of course other bikes on the road and it kept up with anything out there. Okay, it doesn’t have the acceleration of a bigger bike, but its smaller weight more than compensates on a piece of twisty road like this. It climbed those switchbacks effortlessly, had no heating issues despite, I later discovered, being half a quart low on coolant, and gripped the road through those corners. I always knew my bike was easy to ride; the Cabot Trail showed me it’s also very capable.

Finally through Chéticamp, I decided it was time to give both of us a rest. I pulled off at a rest site with a huge mountain lurking over us. The photo does not convey the dimensions and perspective.

As you can see, I left the panniers and top bags at camp. This is another reason why I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck, so I could ride unencumbered. With the switchbacks and challenging section of road behind me, I took a slower pace to complete the loop and returned to camp mid-afternoon. The pool was just the thing after a such an intense, hot ride.

The Cabot Trail was everything I thought it would be. I’m glad I was riding alone and could do it at my pace. I have to add that there was a fair bit of road work happening across the top section, but thankfully it was a section of relatively straight road so was more of an annoyance than a major detraction from the ride. And I guess such an important road for Nova Scotia’s tourism does need to be well maintained. But if you’re not comfortable riding in those grooves or at all on gravel, check highway conditions before you decide to go. But just make sure you do go sometime because it’s a ride not to be missed.

Next up, off-roading in Cape Breton.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

I’d been warned about Bill: the “old man” hauls ass. There were twelve of us, and I decided to tuck in behind him so I could watch and learn. Soon after we pulled out of the ranch I found myself going 70 km/hr on a dirt road with a smattering of gravel. Shit, is it going to be like this all day? I was riding over my head but didn’t want to hold the group up. All was good for a few kilometres until we headed down a sweeping descent. Halfway down I knew I was in trouble. I knew if I braked and turned I would lowside, but fortunately I didn’t panic. I dropped my line and headed straight, gently squeezing the brake. For the first time in my short riding experience the thought that I might crash flashed through my mind, but fortunately I eased to a stop before I ran out of road. Someone behind slowed and gave me the thumbs up as a question. I nodded and looked back. No one was behind me, just empty road. I realized I needn’t have worried about holding the group up because they were all well behind. I had made the classic mistake of trying to keep up with a rider who had 49 years of riding experience on me.

I’d been warned about Bill: the “old man” hauls ass. There were twelve of us, and I decided to tuck in behind him so I could watch and learn. Soon after we pulled out of the ranch I found myself going 70 km/hr on a dirt road with a smattering of gravel. Shit, is it going to be like this all day? I was riding over my head but didn’t want to hold the group up. All was good for a few kilometres until we headed down a sweeping descent. Halfway down I knew I was in trouble. I knew if I braked and turned I would lowside, but fortunately I didn’t panic. I dropped my line and headed straight, gently squeezing the brake. For the first time in my short riding experience the thought that I might crash flashed through my mind, but fortunately I eased to a stop before I ran out of road. Someone behind slowed and gave me the thumbs up as a question. I nodded and looked back. No one was behind me, just empty road. I realized I needn’t have worried about holding the group up because they were all well behind. I had made the classic mistake of trying to keep up with a rider who had 49 years of riding experience on me.

The only problem is that both BMW’s and Touratech’s comfort seats are about $700 CAN. My butt was telling me to spend with abandon, but my mind (and my wife) was reminding me of our budget. Then I heard about

The only problem is that both BMW’s and Touratech’s comfort seats are about $700 CAN. My butt was telling me to spend with abandon, but my mind (and my wife) was reminding me of our budget. Then I heard about