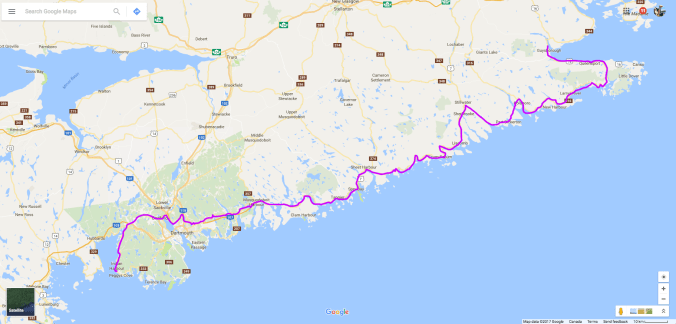

I left Boylston Provincial Park early and headed south along Highway 16 that hugs the coast and curves west. Given how hot it was the day before, I did not make the same mistake but wore my water and dressed lightly. But this is Nova Scotia, after all, and you never know how to dress. In fact, mist hung along the coast and the air was cool, which on the bike is cold. I was freezing. I stopped in Canso for a coffee and to zip the liner into my jacket and change my gloves. I think I might even have turned the heated hand-grips on.

I doubled back along the 16 then turned left onto the 316 that took me west along the southern coast. The ride was magnificent, with inlets and bays on either side of the road.

Sections of Marine Drive carve inland through forested terrain as well, and I was keeping a watch for moose and deer. I took a break at the interpretation centre at Goldboro, where I struck up a conversation with a local who told me the local mine had been bought by a large company and was going to re-open. I can’t remember what kind of mine, but given the name, I guess it was gold. He wasn’t too happy about the prospect of massive trucks rolling past his house at all hours of the day.

Shortly after leaving Goldboro, I turned left onto the 211 and caught a ferry across the inlet.  As I started the bike again when we shored, my gas light came on. I was surprised because I thought I had about another 90 km left in the tank, but then remembered I was off by 50 km. My bike doesn’t have a gas gauge, so I have to keep track of how much gas is left in the tank by using the trip odometer; every time I fill up, I reset it so I know where I’m at. At least, that’s what I always intend to do. For some reason, often I forget this crucial step in the filling process. I don’t know why; it just hasn’t become habit yet. And often there’s a distraction of some sort—the receipt doesn’t print, someone starts asking me questions about the bike, I’m dying to take a piss—and only remember after I’m back on the bike riding. Then I have to reset it while riding, which obviously isn’t ideal.

As I started the bike again when we shored, my gas light came on. I was surprised because I thought I had about another 90 km left in the tank, but then remembered I was off by 50 km. My bike doesn’t have a gas gauge, so I have to keep track of how much gas is left in the tank by using the trip odometer; every time I fill up, I reset it so I know where I’m at. At least, that’s what I always intend to do. For some reason, often I forget this crucial step in the filling process. I don’t know why; it just hasn’t become habit yet. And often there’s a distraction of some sort—the receipt doesn’t print, someone starts asking me questions about the bike, I’m dying to take a piss—and only remember after I’m back on the bike riding. Then I have to reset it while riding, which obviously isn’t ideal.

In this case, it was 50 km into my next segment before I remembered. I made a mental note to add 50 km onto whatever the odometer is reading, then promptly forgot . . . until the gas light came on 50 km “early.” Now I’m in the middle of nowhere running on reserve. I rode for a while but there were no signs that a town was near so I stopped to consult my phone/GPS. Not only was there no gas station, there was no cell service. I was beginning to worry. I had a litre extra on the back of the bike that was good for another 30 km. Then what? I guess start walking.

Just then a guy pulled out of a driveway in his truck. I waved him down and asked where the nearest gas station is. To my relief, I was close. I just had to go a little further, turn left at the T-junction onto Highway 7, and there are two in Sherbrooke. Boy, was I happy to pull into that first station; I’d dodged another gas scare. On this day, I abandoned my goal of finding a nice lunch spot and sat on a public bench at the gas station, de-stressing with my Lunch of Champions.

The ride in the afternoon was along Highway 7. It really is, as Eat, Sleep, Ride describes, “twisties galore.” But now inland, it was hot, and it got hotter as I neared the end of Marine Drive in Dartmouth. I stopped in Lawrencetown to see the famous beach and, a little further on, the kite-surfers.

By the time I entered Cole Harbour, thinking of hockey, it was easily 30 degrees Celcius and who-knows-what on the humidex scale, probably upper 30s. Then I hit traffic. Ugh! It was rush hour so I decided to skirt Dartmouth and followed a route that looped over the top through Bedford on the 213 that took me to within 15 minutes of Peggy’s Cove at Wayside Campground.

I’d found Wayside online when I changed my plans at Baddeck and decided to visit Peggy’s Cove. The reviews said it was a campground run by the same family for generations and was very family-oriented. In fact, one reviewer had given it a bad review because his group had apparently been refused a site on the suspicion that they were there to party. (Is that a negative or positive review? I guess it depends on if you like peace and quiet at a campground.) At any rate, I wasn’t sure what to expect when I pulled up on my motorcycle. I was greeted at the office by several of said family members sitting on the porch. The manager was super friendly, and as I was filling out the paperwork, her son showed me a photo on his phone of a cousin’s BMW ADV bike (I think it was the 800GS) and told me a story of an aborted trip to Alaska. Seems I would not be refused a site for being a trouble-maker biker, and good thing too because I was hot and exhausted. The manager clearly knew a thing or two herself about bikes because she warned me about the rocky hill to get to some of the tent sites on the plateau.

Remembering my dismount mishap at Deer Island, I made sure to concentrate right until the kickstand is down. Not long after it was, another camper named Walter wandered over from his RV and handed me a cold can of beer. I’d say he must have read my mind, but his knowing my needs actually has a simpler explanation. Turns out he used to ride a Kawasaki KLR 650, so knows every biker’s first thought at the end of a long, hot ride. He was retired military from the Air Force, and he and his wife Barb summer in Nova Scotia.

The next day I woke up early (like, 6 a.m.), and although I planned to leave that day, I decided to drop everything and head to Peggy’s Cove after a quick breakfast. I have to admit, I wasn’t all that drawn to Peggy’s Cove, but thought I should check it out because it was such an iconic tourist spot. I envisioned busloads of tourists crawling over the rocks (if the sea doesn’t wash them off first) and tacky tourist shops filled with plastic replica lighthouses. Thankfully, that vision was entirely wrong! It’s actually a very pretty little fishing village that has been carefully preserved. I did manage to catch the lighthouse before the throngs, and the image above is my proof.

The rest of the village is almost as pretty.

The memorial to the passengers of Swissair Flight 111 is also tastefully done. It’s just on the other side of the cove in a quiet spot more suiting to reflection and remembrance. Two disks are placed on end and angled such that if you look down them, one points to Bayswater and the other out to the crash site on the horizon. The three geographical points, including Peggy’s Cove, form a triangle that was instrumental in the investigation as the area covering the debris field.

I’m sure the final moments of those unfortunate passengers were terrifying, but there are few prettier places to leave this Earth in bodily form. I’m glad I went to Peggy’s Cove. My prejudice of it and private campgrounds like Wayside were happily quashed.

Next day, Bigbea gets an oil change in Moncton and we head to Fundy National Park.

Sites are administered on an honour system at a whopping $21.60 a night tax included. They are grassy and private and quiet. If you’re ever in the area, be sure to stay at Boylston. She then proceeded to tell me where to find a micro-brewery pub with “the best fish and chips in the province.” If I hadn’t already been married, I might have proposed.

Sites are administered on an honour system at a whopping $21.60 a night tax included. They are grassy and private and quiet. If you’re ever in the area, be sure to stay at Boylston. She then proceeded to tell me where to find a micro-brewery pub with “the best fish and chips in the province.” If I hadn’t already been married, I might have proposed.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

I’m not sure why it’s called the Sunrise Trail since it faces northwest, not east, but it’s pretty nonetheless. At one point, just west of Arisaig, I saw a dirt road leading off from the 245 and decided to go exploring. This is what I love about adventure riding and my bike—the ability to get off the asphalt when curiosity beckons. A short ride in led to a perfect lunch spot overlooking the ocean, complete with a picnic table to prepare my sandwich.

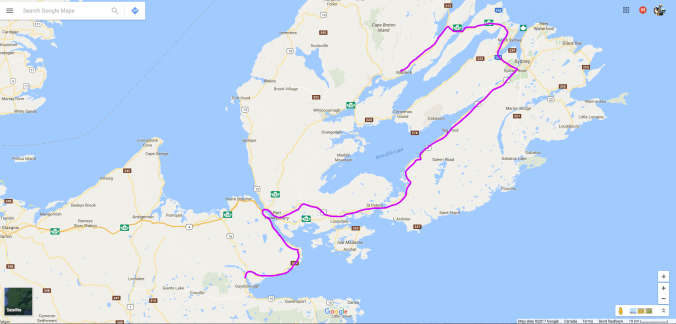

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.

I love this campground! My wife and I stayed here when we vacationed in Cape Breton two years ago, and she found it, so I can’t take any credit. It’s a very well run campground with wooded sites, clean washrooms, friendly service, a heated pool (nice after a long day of riding), free showers and, a personal favourite of mine, a campers’ lounge. I have to admit, I didn’t take to the lounge right away; it has a TV and seemed like what one tries to escape by camping. But this time round I was forced to sit there to charge my phone, and found it a pleasant place to write or read, especially on the evening it rained. I decided to stay an extra night at Baddeck.