Voyageur Days. Mattawa, ON

What’s your ideal ride? For some, it’s a winding road like Tail of the Dragon; for others, it’s a single-track or ATV trail cutting through dense forest. Mine is some combination of both—a winding dirt road with some technical sections that challenge, like hill-climbs, mud, even the occasional water crossing. That’s what I was looking for when I decided to do some off-roading in Northern Ontario this summer.

I enjoyed looping Georgian Bay with my wife, and I enjoyed the rest stop in Kipawa, Quebec, at a cottage. I enjoyed the ride up to Moonbeam, albeit in the rain. But what I had really been looking forward to is a full day in the dirt, and this was the day I could finally do it.

The violent rainstorm of the night before had subsided by the time I crawled out of my tent. After my breakfast of champions, porridge, I geared up and headed to the park gate. I figured the attendant would be familiar with the area and able to direct me to the trailhead of The Lumberjack Trail, a 26 km. loop from Moonbeam to Kapuskasing I’d found online at an interactive trip planner.

Lumberjack Kapuskasing-Moonbeam Loop

I rode down to the gate, pulled a U-turn and parked. When I entered the kiosk, the young lady was staring into her phone. Our conversation went something like this:

Me: “Good morning. Do you know where I could pick up The Lumberjack Trail?”

Teenaged attendant: (looks up from phone) “The what?”

Me: “The Lumberjack Trail. It’s an off-road trail that goes from here to Kapuskasing. I saw it online.”

Teenaged attendant: (goes back to phone) “Ok Google, what’s The Lumberjack Trail?”

Me: “You don’t know it?”

Attendant: “There’s a lot of trails around here. Basically it’s the only thing to do. Me and my friends go on them on the weekends.”

Me: “Oh, so you ride off-road too?”

Attendant: “No we go in cars. Anything.”

Me: “Well, it’s supposed to go right past here.”

Attendant: “There’s a really pretty one. It’s a . . . a pépinière. Oh, how do you call it in English? Ok Google . . .”

Me: “A nursery.”

Attendant: “Yes. There are a lot of pine trees. But I don’t know how to find it. Try the Tourist Information.”

So off I rode, back to the flying saucer, pondering whether I should ask for directions to the Lumberjack Trail, the Pépinière Trail, the Nursery Trail, or a pine grove?

Once there, I was quickly directed to the trailhead. It turns out that you follow Nursery Road and it takes you straight there.

This looked promising

A short ways in, the trail became sandy and I found the pine trees.

The Nursery Trail

It was open and easy, but with sand and some small hills to make it a Goldilocks level of difficulty. Unfortunately, it ended too soon. I arrived at a T-junction to a gravel road. Knowing that left leads back to the main road, I turned right and found myself on an open, flat, fairly straight dirt road.

The surroundings were pretty enough, but the riding was not very challenging. I was a bit disappointed. It was too easy. It’s actually hard to find a trail with just the right amount of challenge for your particular skill level, and where the Nursery Trail had at least some sand, this road was dry and hard-packed. I was bombing along in third gear, not even standing, thinking “This is too easy” when I hit a section still wet from the rainstorm the previous night. Everything suddenly went sideways—literally. A truck or larger vehicle of some kind had come through before me and left tire grooves. I started to lose the back end, went sideways, got cross-rutted, whiskey throttled towards the trees, and went down high-side, hard. It was my hardest fall yet.

My first thought as I lay on the ground was, “Well, the gear worked.” I had invested earlier in the season in some excellent protection specifically for off-roading. My Knox Venture Shirt, Forcefield Limb Tubes, and Klim D30 hip pads all did their job. I got up without even a bruise. My second thought was for the bike. If there was something broken, it was going to be difficult to get it out. I noticed that the folding levers I had also invested in had done their job. The clutch lever was folded up, saving the lever from breaking off. I lifted the bike and took a look. Nothing was broken or cracked; the crash bars had done their job too. There were some new scratches on the windscreen and front cowling near the headlamp, but nothing more. Oh well, new honour badges, I thought.

My concern now was getting the bike back on the road. I was lucky: if I’d gone a few feet further I might have lost it into a ditch and then would have needed a winch to get it out.

Once I lifted the bike, I realized it was going to be difficult to get it back onto the road.

The front end was partially into the ditch and it would take some rocking and cursing to get it back a few feet to where I could carefully walk it back onto the road, making sure the front tire didn’t slide down.

I looked back at my skid marks and played amateur accident inspector.

You can see where it all went wrong.

I tried to ride on but the silty dirt, when wet, is like glue and gums up the tires instantly. It was like riding on ball bearings, or rather, trying to ride on ball bearings.

Slow-going in the wet silt

The ride now certainly wasn’t too easy. I basically had to do the Harley waddle, foot by foot, hoping it would get drier. I tried riding along the edge of the road in the long grass, thinking the grass would provide some grip, but the problem then was that I couldn’t see what I was riding over or where the ditch was. I dropped the bike a second time and began to wonder how I was going to get out of there. Would it be like this all the way to Kapuskasing?!

Then I had an idea: I knew that in sand you put your weight to the back to unweight the front tire. This helps prevent the front from washing out, which is when you go down. Maybe the same technique applied to all low-traction terrain, including mud. I tried and it worked! The front tire didn’t wash out as easily, even, to my surprise, climbed up out of some small ruts when needed. I had stumbled upon a new off-road skill.

When the road dried out, I was able to sit down, but kept my butt well back, over the rear tire. It all suddenly made sense why those Dakar riders always sit so far back. Now I was able to go at a better pace. The rest of the road wasn’t as wet as that section and, although open and straight, turned out to be just challenging enough. I stopped a few times when I saw some interesting paw prints.

Bear prints. I also saw wolf and hare tracks.

When I felt I was past the worst of it, I stopped for lunch and took in the surrounding wetlands.

Wetlands north of René Brunelle Provincial Park

I popped out in Kapuskasing next to the Shell station on Highway 11. Although there was a sense of incompletion in only doing one half of the loop, I decided that was enough excitement for one day and headed into town to find the LCBO and something to enjoy back at camp. I wanted to explore the town a bit and was glad I did. Kapuskasing has an iconic ring of Canadiana to it.

I had the impression that it was bigger than it is, but there isn’t much in these parts that is big. These one-industry towns in the north are built on mining or forestry and are pretty remote. I rode through the town centre, which is a roundabout, and landed at the train station, the heart of all Canadian towns.

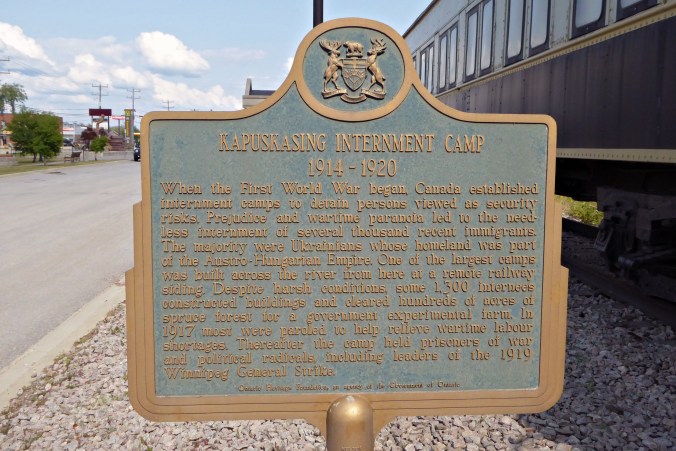

Surrounding the station were archival photos of the town and area, and I discovered that Kapuskasing had been the site of an internment camp during WWI. Primarily Ukrainian immigrants were shamefully sent there to work in a government-run experimental farm studying the viability of farming on clay. Later in the war it was a POW camp.

Surrounding the station were archival photos of the town and area, and I discovered that Kapuskasing had been the site of an internment camp during WWI. Primarily Ukrainian immigrants were shamefully sent there to work in a government-run experimental farm studying the viability of farming on clay. Later in the war it was a POW camp.

A plaque outside the train station commemorates the Kapuskasing Internment Camp, 1914-1920

I love Canada and am a proud Canadian, but every nation has its dirty little secrets hidden in untaught history classes. Currently in Quebec, some teachers have expressed serious concern that the role of minorities is overlooked in the current history curriculum. I believe that a little less Upper and Lower Canada and the harmonious relationship with Indigenous Peoples, and a little more on the Indian Residential Schools (IRS), the internment camps of law-abiding citizens during both world wars, and the not-so-quiet actions of the FLQ in the 70’s would go a long way toward real truth and reconciliation among its diverse peoples.

I left the station and rode to the City Hall, then parked and walked out to a gazebo overlooking the river and mill. I came across this plaque about the Garden City and Model Town, and it occurred to me how much promise and hope there must have been in Kapuskasing at one time.

Maybe Kapuskasing is iconic. It could be symbolic of how the country seemed when Europeans began settling here—pristine, pure, wild—like the blank page awaiting our best intentions. But intentions are just a start. The real work happens after the first draft, when we see all our mistakes and how we can make it so much better.

It climbs as it heads north, opening up into farmland and views of the distant mountains.

It climbs as it heads north, opening up into farmland and views of the distant mountains.

I grew up hearing of the Bruce Peninsula. My dad sometimes worked at the

I grew up hearing of the Bruce Peninsula. My dad sometimes worked at the

It’s been over a month since my last post and only the third really this season. Yes, I’ve been a bit lazy lately as a writer but only because I’ve been hard-working as a rider. Ideally I like to write about my time on the bike as soon as possible afterwards, but this year a few commitments got in the way. One in fact was

It’s been over a month since my last post and only the third really this season. Yes, I’ve been a bit lazy lately as a writer but only because I’ve been hard-working as a rider. Ideally I like to write about my time on the bike as soon as possible afterwards, but this year a few commitments got in the way. One in fact was

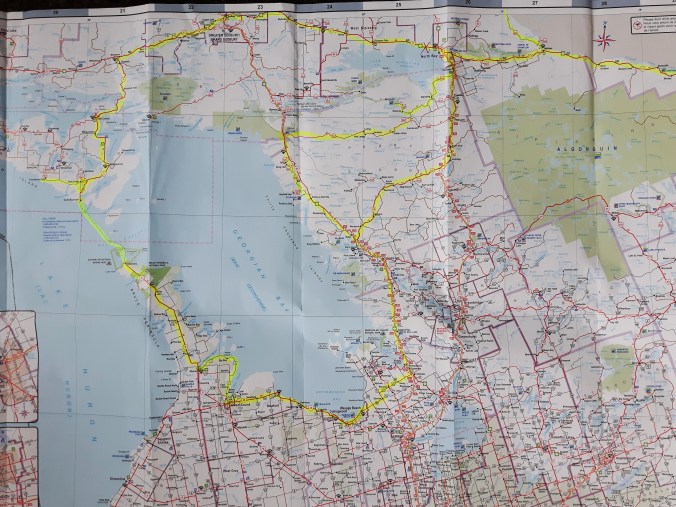

How much planning do you do before heading off on a tour? Do you have your entire route determined with accommodations booked, or do you leave a little to chance and exploration? Is your trip fixed in asphalt or is it flexible, able to change when the spirit moves you or weather or some other factor meddles with your plans? There is security in knowing where you’re going and that there’s a reserved room waiting for you at the end of a long day of riding, but there’s risk and excitement in leaving some room for chance; sometimes the most memorable moments are gained through the unexpected.

How much planning do you do before heading off on a tour? Do you have your entire route determined with accommodations booked, or do you leave a little to chance and exploration? Is your trip fixed in asphalt or is it flexible, able to change when the spirit moves you or weather or some other factor meddles with your plans? There is security in knowing where you’re going and that there’s a reserved room waiting for you at the end of a long day of riding, but there’s risk and excitement in leaving some room for chance; sometimes the most memorable moments are gained through the unexpected.

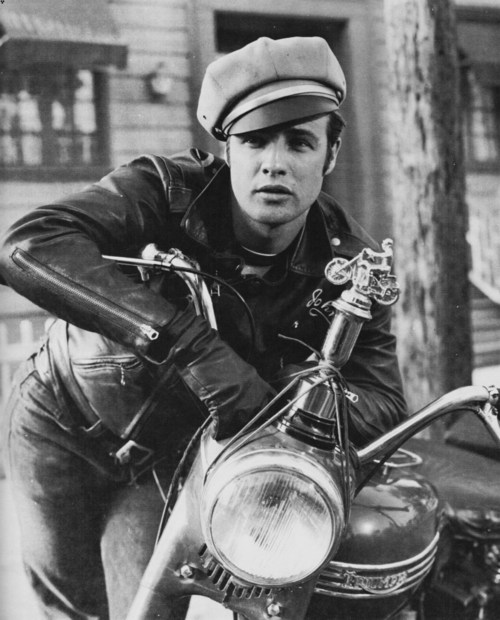

Bikers have always been on the periphery of society, seen as rebels. It’s not surprising that some of the most iconic images of rebelliousness include a motorcycle. I’m thinking of James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, or am I confusing that iconic photo of Dean on his bike with Marlon Brando on his in On the Waterfront? In both cases, there was a rebel, a leather jacket, and a motorcycle. It’s clearly this image that the folks at Harley Davidson have exploited as the focus of their hugely successful marketing campaign. And it’s this image that the weekend warriors embrace as they head out to Timmies (or Starbucks) on a Saturday afternoon.

Bikers have always been on the periphery of society, seen as rebels. It’s not surprising that some of the most iconic images of rebelliousness include a motorcycle. I’m thinking of James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, or am I confusing that iconic photo of Dean on his bike with Marlon Brando on his in On the Waterfront? In both cases, there was a rebel, a leather jacket, and a motorcycle. It’s clearly this image that the folks at Harley Davidson have exploited as the focus of their hugely successful marketing campaign. And it’s this image that the weekend warriors embrace as they head out to Timmies (or Starbucks) on a Saturday afternoon.

I’ve always said I love my little thumper, but if it’s done one thing for me it’s to get the off-road hook sunk deep. My first two years of riding have been a slow gravitation toward off-roading simply because the challenge and possibilities are endless. It’s also pretty exhilarating when you slide out the back end going around a corner on a gravel road, or charge up a rocky hill climb, or feel the bike slide around beneath you through some mud. The Africa Twin is the off-roader’s adventure bike. I sat on the Triumph Tiger 1200 and you know what? I wouldn’t want to be taking that beast off-road.

I’ve always said I love my little thumper, but if it’s done one thing for me it’s to get the off-road hook sunk deep. My first two years of riding have been a slow gravitation toward off-roading simply because the challenge and possibilities are endless. It’s also pretty exhilarating when you slide out the back end going around a corner on a gravel road, or charge up a rocky hill climb, or feel the bike slide around beneath you through some mud. The Africa Twin is the off-roader’s adventure bike. I sat on the Triumph Tiger 1200 and you know what? I wouldn’t want to be taking that beast off-road.  I imagine the BMW 1200 is the same. There’s just no room for error with all the weight. And don’t try to tell me you don’t feel the weight because it’s so nicely balanced. The first time you and the bike get kicked sideways off a large rock that rolls away from under you, you’ll feel the weight, all 580 lbs. of it as you lift it up. The Africa Twin, on the other hand, is 507 lbs., a full 73 lbs. lighter thanks to it’s smaller 999cc engine—more than enough to get you to the Timmies of your choice. But where the Africa Twin really shows its off-road colours is with the wheel size: 21” front and 18” rear. Compare that to 19” front and 17” rear in the R1200GSA and you know why the ground clearance is 9.8” compared to 8.5”. As far as I’m concerned, the 12000GSA is the bike for long adventures in remote areas, but I wouldn’t want to take it anywhere more remote than a dirt road. The 800GS is the true BMW adventure bike.

I imagine the BMW 1200 is the same. There’s just no room for error with all the weight. And don’t try to tell me you don’t feel the weight because it’s so nicely balanced. The first time you and the bike get kicked sideways off a large rock that rolls away from under you, you’ll feel the weight, all 580 lbs. of it as you lift it up. The Africa Twin, on the other hand, is 507 lbs., a full 73 lbs. lighter thanks to it’s smaller 999cc engine—more than enough to get you to the Timmies of your choice. But where the Africa Twin really shows its off-road colours is with the wheel size: 21” front and 18” rear. Compare that to 19” front and 17” rear in the R1200GSA and you know why the ground clearance is 9.8” compared to 8.5”. As far as I’m concerned, the 12000GSA is the bike for long adventures in remote areas, but I wouldn’t want to take it anywhere more remote than a dirt road. The 800GS is the true BMW adventure bike.

Only 250cc., you say? This easily does 120 km/hr. on the highway and tops out at 140, but if you’re riding a 250 you probably aren’t riding the highway anyway. Only as much as necessary. You can put a tail rack on this baby, some soft panniers, and hit the Trans-Am Trail, or The Great Trail in Canada, for that matter.

Only 250cc., you say? This easily does 120 km/hr. on the highway and tops out at 140, but if you’re riding a 250 you probably aren’t riding the highway anyway. Only as much as necessary. You can put a tail rack on this baby, some soft panniers, and hit the Trans-Am Trail, or The Great Trail in Canada, for that matter.  This little bike is a dirt-bike on steroids, capable of adventure too if you’re not in a hurry. And at only 235 lbs., it would be a fun and safe starter bike. The other option at Honda is the “adventure styled” CB500X.

This little bike is a dirt-bike on steroids, capable of adventure too if you’re not in a hurry. And at only 235 lbs., it would be a fun and safe starter bike. The other option at Honda is the “adventure styled” CB500X.  With cast wheels and a lowish ground clearance, this is clearly a street bike. But with the

With cast wheels and a lowish ground clearance, this is clearly a street bike. But with the  But then the silver, brushed metal tank is pretty cool too, harkening back to those old Norton tanks.

But then the silver, brushed metal tank is pretty cool too, harkening back to those old Norton tanks.  Or the one with black and gold highlights.

Or the one with black and gold highlights.  But my favourite, if we are posing, is the Racer with the retro colours and bubble cockpit. This would definitely turn some heads.

But my favourite, if we are posing, is the Racer with the retro colours and bubble cockpit. This would definitely turn some heads.

It tries too hard. The whole secret of a poser bike is getting one that looks great but not too great, if you know what I mean. It’s a sign of desperation. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never been drawn to Harley Davidson, and you’ll notice there are no photos here of them. The only photos I took at the Harley display was of the entire display, complete with rock music, large-screen video, lots of leather, and Harley chicks in skimpy skirts. They are clearly selling a lifestyle. It’s a sight to behold. But if I were forced to chose another bike, less practical than my adventure bike, but that looks great, I’d be more inclined to go with something like the Triumph T100 or the Street Twin. Classic, classy, and modern, all in one package.

It tries too hard. The whole secret of a poser bike is getting one that looks great but not too great, if you know what I mean. It’s a sign of desperation. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never been drawn to Harley Davidson, and you’ll notice there are no photos here of them. The only photos I took at the Harley display was of the entire display, complete with rock music, large-screen video, lots of leather, and Harley chicks in skimpy skirts. They are clearly selling a lifestyle. It’s a sight to behold. But if I were forced to chose another bike, less practical than my adventure bike, but that looks great, I’d be more inclined to go with something like the Triumph T100 or the Street Twin. Classic, classy, and modern, all in one package.  Triumph should be applauded for bringing back these classic bikes but seamlessly incorporating all the benefits of modern technology. And they get it right with the analog display, round headlight, and fork gaiters.

Triumph should be applauded for bringing back these classic bikes but seamlessly incorporating all the benefits of modern technology. And they get it right with the analog display, round headlight, and fork gaiters. The ergonomics are perfect and the seat is wide and comfy. Unlike BMW, Kawasaki have designed their way out of the comfort saddle aftermarket, to their credit. They know their clientele. Then he looked at the price: a little over $7,000. Compare that to the “comparable” 750GS at almost $11,000. That’s about $4,000 more, a lot of money when you are a student. Okay, the 310R, wherever it is, is $6,450, but has half the power and cast rather than spoke wheels. I’d take the KLR any day, but God-forbid not that ugly Camo version. What were they thinking?

The ergonomics are perfect and the seat is wide and comfy. Unlike BMW, Kawasaki have designed their way out of the comfort saddle aftermarket, to their credit. They know their clientele. Then he looked at the price: a little over $7,000. Compare that to the “comparable” 750GS at almost $11,000. That’s about $4,000 more, a lot of money when you are a student. Okay, the 310R, wherever it is, is $6,450, but has half the power and cast rather than spoke wheels. I’d take the KLR any day, but God-forbid not that ugly Camo version. What were they thinking?

Designed by a small, very specialized team, the bike is BMW’s pure-bred racer, and here was one of only 750 made. No wonder we were not allowed to sit on it. Back down on earth, we looped back around to Honda to look at the new Gold Wing.

Designed by a small, very specialized team, the bike is BMW’s pure-bred racer, and here was one of only 750 made. No wonder we were not allowed to sit on it. Back down on earth, we looped back around to Honda to look at the new Gold Wing.