Street woodcarving in Mattawa, Ontario

After playing in the dirt around Moonbeam, I decided to head over to Cochrane to check out the Cochrane Polar Bear Habitat. It’s the world’s largest and only human care facility dedicated to polar bears. They are located on 7 hectares of natural terrain and currently have three resident polar bears. I’m not a fan of zoos but these bears can’t survive in the wild and require human care; they were all either born in captivity or orphaned. The Habitat also advocates and educates towards protecting polar bears and their natural spaces.

It was an easy ride east along Highway 11 from my campground in Moonbeam to Cochrane. I stopped at Smoothy’s in Smooth Rock Falls for gas and breakfast.

Smoothy’s Family Restaurant; Smooth Rock Falls, ON

Okay, they don’t win the award for most original name, but Smoothy’s was just what I was looking for: a classic diner where I could get an inexpensive bacon & egg breakfast with fried potatoes on the side. In the booth next to me were four retired men speaking French. In fact, pretty much all I’d heard this trip was French—in Iroquois Falls, in Moonbeam, in Kapuskasing. I’d never realized how big the Franco-Ontarian population is! A few Anglicisms had crept into their French, but I was surprised that the language and culture seems to be surviving just fine without any Bill 101 and its ridiculous sign laws or restricted access to education in English like we have in Quebec. Having said that, I must add that this past fall the new premier of Ontario decided to cut the French Commissioner position, a slap in the face of Franco-Ontarians and a sign of how vulnerable the French population is outside Quebec. Fortunately, Premier Ford reversed his decision a short time later, I don’t know whether due to pressure from Prime Minister Trudeau, public outcry, or common sense, once someone showed him the numbers and how such a decision would hurt him in the next election.

Another interesting cultural observation I had while up north was this billboard that I kept seeing.

I’ve never seen anything like it around Montreal or southwestern Ontario. I’m not sure who the target population is, whether residential school survivors or men in general, but I think it’s high time we begin to discuss men’s issues, including sexual abuse.

With both bike and belly full, I pushed on to the Polar Bear Habitat in Cochrane. I arrived mid-morning and a tour had just started. “Run through to the first building and you can catch up to the group,” the lady at the entrance advised. So I did, only partway between buildings I was stopped in my tracks by the sight of two bears against the fence. They were huge! And exactly as you would expect with that distinctive long neck and pointed head, and not expect. Their fur is not so much white as golden, and their eyes and ears seem so small compared to their massive bodies, no doubt evolved to cope with blinding, blowing snow. I just stood there and watched them for a minute before heading in to catch up with the tour.

The Habitat currently has three bears on location: Ganuk, Henry, and Inukshuk. Inukshuk, whose mother was shot when he was just four months old, is the father of Henry, bred when Inukshuk was at Zoo Sauvage in St Felicien, Quebec. Each bear has a unique personality and food favourites.

The facility is impressive, with natural and artificial areas, and a pool with a glass wall so you can see the bears swim underwater if they are in the mood. There are interactive learning stations for the kids and lots of information available on the walls and other exhibits for the studious, but really, everyone mostly just wants to look at the bears. They are magnificent!

Our guide reminded us that although they look cute and cuddly, the bears are dangerous and no one is ever alone with them on the inside of the fence which, we were told, is unbelievably more to keep people out than the bears in! They have had instances of people climbing in, I guess like the idiot videoed recently swimming nude with the sharks at Ripley’s Zoo in Toronto. Some people have the most warped sense of judgment when playing Truth or Dare after a few beers.

When the bears decided to head down to the natural pond, disappearing into the trees, I decided to step back in time a hundred years and headed over to Heritage Village. (Visitors to the Polar Bear Habitat also have access to Heritage Village and a snowmobile museum.) The village looks authentic and has been used for film sets. It includes a general store, butcher’s shop, doctor’s office, blacksmith’s shop, fire station, schoolhouse, and trapper’s cabin.

No rollerball razors here. You can almost smell the lather and tonic.

While not the impetus of my visit, the Heritage Museum was interesting. It’s one thing to learn about history from a textbook or historical movie and another to see the physical artifacts of another era and another way of life. The buildings have been authentically decorated to assist the imagination in conjuring an ordinary day in the life of early 20th-Century citizens. When I returned to the bears, one of them was being fed strawberries through the fence.

Staff feed the bear while children watch on.

Before leaving, I wandered into the snowmobile museum. I imagine Cochrane has quite the snowmobile culture during the winter months, and it’s a good idea to preserve some of these machines here for posterity. Each is labelled with year, model, and owner name.

Each represents the cutting-edge technology of its day.

I started back toward camp but this time, as I passed through Smooth Rock Falls, I saw a sign for Lookout Road. Assuming it led to its namesake, I pulled off and headed up a dirt road; it was the adventure bug again. At the fork in the road, I went left and the road slowly deteriorated into a trail.

Another promising trail to follow. Would it lead to the lookout?

I was on my own and without a Spot device, so venturing along an unknown trail deeper into the bush was both exciting and unnerving. My worst fear was that I might find myself in a situation from which I couldn’t get back to the road, kind of like what almost happened when I had my off on the Lumberjack Trail, but hey, Lyndon Poskitt and many others are adventuring around the world solo so I figured I’d venture a little further along this trail. There were some muddy sections and some hills but my curiosity pulled me deeper, farther away from the road. The trail opened up into a meadow at one point, and then descended again into the trees, leading to this muddy puddle blocking the way.

End of the line for this solo rider.

I wasn’t so much worried about going down those logs into the water as getting back. If I hadn’t been on my own, I would have gone for it, but since discretion is the better part of valour, I decided to turn back here.

Once I got back to the Y in the road, I realized that the lookout was just a hundred yards further along to the right. Doh!

The view was worth every misdirected inch to reach it.

The next day I started home. I had about 1000 km to cover in two days. I took the 11 east to the 655 south, which took me into Timmons. Traffic through Timmons was stop and go but there was no time to stop because I was trying to reach Dynamic Earth before it closed. After my experience in the coal mine at Springfield, NS, I wanted to go down into another, and Dynamic Earth offers a tour into the nickel mine there.

A little jog along the 101 at Timmons and soon I was on the 144 south. The 144 is another of Ontario’s great roads to ride. It’s a two-lane highway that cuts through precambrian rock as it descends down toward Sudbury. There’s a mixture of straight sections but the real fun is with the large sweepers. The highway is immaculately maintained with no pot-holes or tar snakes to worry you, and surrounding scenery is pure bush, so enjoy but keep your eye out for wildlife.

I stopped at the Tim’s just outside of Sudbury. It had been raining and again my phone was not charging. I gave it a quick charge at Tim’s, but I had to keep it short if I was going to catch a tour. I didn’t want to do the tour the next morning since I had a long way still to reach my home in Montreal. As I pulled out of Tim’s and cracked the throttle, the bike lurched and the tachometer suddenly read twice what the bike was revving. It was up in the red! I’d only seen this once before and didn’t know what it meant but did what I had done that first time: I hit the kill switch, let the ECU sort itself out, and restarted. Everything was fine and I got to the mine in time to catch the last tour of the day.

Big Nickel at Dynamic Earth

We were given hardhats and descended 7 stories underground where the temperature is about 13C (55F). The tour takes about 1 hour and 15 minutes and shows visitors what mining was like from the earliest days at the turn of the century to today.

In the footsteps of Sudbury’s miners.

The young guide was knowledgeable and informative, and the tour was animated with video installations and mock explosions. I could see how technology has evolved over the century to create a safer and more efficient work environment. Canada also has evolved over the century and now its economy is more diversified than before, but the country is renowned for its natural resources. It was opened by the fur trade, with forestry and mining the other big resources that followed. I’m glad I experienced this important part of Canadian history while I was at one of the country’s largest mines. The Sudbury mine has over 5,000 kilometres of tunnels; placed end to end, you could drive from Sudbury to Vancouver underground!

When we returned above, it was late in the afternoon and I was tired from the race down from Moonbeam. Although Dynamic Earth has a lot more to offer than the mine, I decided that was enough for one day and headed to a campground I’d found online. While en route my bike did that lurching tachometer thing again, and then my phone finally died. Fortunately, I’d packed a car GPS as a backup and it got me there.

The next morning I left Sudbury and headed east along the 17, the Trans Canada Highway, into North Bay. I decided that the 533, although out of my way, was just too good to pass up, so I turned north onto the 63. As I did, I saw a woman rider by the side of the road on her phone. Naturally, I stopped to see if she needed some help. The chain had come off her Kawasaki 650 Ninja. She was trying to reach the local garage but no one there was answering. She told me her male friend did all the maintenance on the bike for her and she didn’t have a clue how to tighten the chain. I’m always surprised that some riders, male or female, don’t know how to do the basics. It just seems that you would always be so vulnerable, but then again, I guess the vast majority of drivers don’t know even how to jump-start a car, so perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised.

I tightened everything up for her and headed on my way, not knowing that soon I’d be in the same situation. As I was enjoying the 533 east, the bike surged and the tach jumped to double again. This time, rather than resetting the ECU with the kill switch, as I’d done before, I decided just to let the bike run as is; I knew the engine wasn’t revving that high—the tachometer was giving a false reading—so I kept going. The 533 is the twistiest piece of road I’ve ever ridden and a lot of fun, but I soon decided to take it easy since the bike was surging and lurching more and I couldn’t trust it. As I came down into Mattawa it stalled. I restarted it and drove another hundred yards and then it died again. As I rode the main strip in Mattawa, it died on me several more times and then I couldn’t restart it so I coasted in to a spot at the side of the road beside an entrance. As I did, I noticed a BMW 1200GS on the other side of the entrance, so we were the BMW bookends of this particular drive.

No sooner had I removed my top bag and dug out my tools than I heard a voice say “You’re missing a cylinder.” It was the owner of the 1200 and he introduced himself as John. He hadn’t seen me limp into town so I explained the situation. Being an ADV rider himself, he naturally said I could crash at his place in North Bay if needed and use his tools to fix the bike. He thought it might be the regulator. I thought it was a plugged fuel filter. I stripped the bike of the plastics and pulled the cover off the fuel supply, cleaned the filter and put everything back. The bike started and idled okay. Only before setting off, I had the voice of the Jack Nicholson character in the movie Bucket List in my head, “Never pass up a bathroom,” so I killed the engine and took care of business. When I returned to the bike, it wouldn’t start. Dead battery. Completely dead. Things were going from bad to worse.

I asked John for a push to bump start the bike. We must have been a sight heading up the main drag, me on the bike, he pushing from the back. The bike started but I couldn’t keep it running. As soon as the revs dropped to idle it died. Then we couldn’t start it at all. Fortunately my spot was still vacant so I coasted back, stripped the bike again, and removed the battery. John suggested I take it to the garage on the corner and get a quick charge on it.

Curb-side maintenance on Bigby.

Now I had an hour to kill so I grabbed some poutine from the local chip stand and watched the lumberjack races. It was Voyageur Days in Mattawa.

Audience participation at Voyageur Days

I wandered up to the local Tim’s and, while walking back, saw John as he was heading back to North Bay. He repeated his offer if I couldn’t solve my problems.

When I got to the garage, the owner-mechanic was gone.

“He went to the fights,” the young lady running the gas bar said.

“The what?”

“The fights. There are fights tonight.”

I was trying to imagine what kind of fights would be in Mattawa but eventually just helped myself to my battery, which was still on the charger. It was $10 for the charge.

I got back to my bike and installed the battery, replaced all the plastics and loaded the bike again. Now was the moment of truth. I turned the key and hit the starter: the bike made a grunt. Hmm . . . I guess I’m staying in North Bay tonight. Then I hit the starter again and it fired! It idled!

I know now what the problem was. I had been charging my phone off the battery throughout the trip, sometimes even when the bike wasn’t running because I needed it. I should have known that the battery is only for starting the bike, not a portable power supply. All that charging had boiled three of the cells dry. The morning of my problems, it was cold and I had the phone charging and the hand warmers on high. The charging system couldn’t keep up and the battery got further drained. When the battery dies, the instrument panel starts doing crazy things and the ECU acts up. The single source of my problems—the surging, the weird tach readings, the eventual non-starting—was a weak battery.

I now finally started heading home. At that time, I still wasn’t sure if the regulator was acting up and if the battery would drain while riding to Montreal. I kept a constant speed and didn’t ask much of the bike. I stopped only twice. Both times I kept the bike running because I wasn’t sure it would start again. I even kept the bike idling while filling it. Who’s going to stop me?

Just outside of Ottawa, I nipped into a convenience store to use the bathroom. When I came back outside, a brown liquid was pouring from underneath the bike. Problems on top of problems! My first thought was oil leak. I dipped my fingers into the puddle; it smelt like gasoline. Perhaps I overfilled it? Did it have something to do with not turning off the bike while filling? I wasn’t sure but now had extra incentive to get home. Fortunately, when I straightened the bike up off the side stand, the flow of brown liquid stopped. If I could keep the bike relatively upright, I could get home. I’ve never had such a stressful ride!

Again, I now know what was happening. Earlier in the summer, I’d had the bike on its side for the better part of a day. Oil had drained into the air box and the brownish liquid draining from beneath the bike was from the drain tube. I’m still not sure why it smelled like gas or why it was only draining now, but it was not coming from the engine. It was draining from the air box.

I pressed onward, ever closer to home, keeping an eye on my instrument panel, half-expecting the oil light to come on. Each kilometre, I thought, was one less kilometre my wife would have to travel with a trailer to pick me and Bigby up. I was hoping to keep a steady speed all the way, but as luck would have it, the major highway passing through Ottawa was closed! It was stop and go traffic for miles as we were rerouted through downtown Ottawa, adding hours onto my trip. What a day!

Once back on the highway, it was smooth-riding. As I approached the border into Quebec, I could see lightening flashes in the distance ahead. Riding into a thunderstorm seemed the perfect climax to a stressful day, but thankfully it opened up just as I pulled into my driveway. My guardian angel had gotten me home again—and not a moment too soon.

Riding an old bike has its disadvantages, for sure, but I have to admit that the problems of the day were more my fault than the bike’s. I depleted the battery by using it to charge my phone, and I forgot to clean the airbox after the bike had been on its side. In the end, I was super lucky that Bigby conked out where he did, in Mattawa, with a mechanic on duty and John for support and advice, not on the 533 where there isn’t even cell service.

Each time I tour, I learn a little more about the bike and about riding. I’m building my knowledge in lower-risk places close to help. And each year I venture a little further off the asphalt. I’m already planning next year’s tour that will take me deeper into the bush and into more challenging terrain. Who knows where I might end up? I don’t know where I’m headed but I almost always enjoy the ride.

46.317480

-78.702193

Soon some more riders caught up to me with the same idea. I met Nigel and his dad and a few friends on their classic BMWs. Nigel has a 1977 R100 RS, and his dad has a 1980’s era BMW. Someone else in the group has the new Royal Enfield Himalayan.

Soon some more riders caught up to me with the same idea. I met Nigel and his dad and a few friends on their classic BMWs. Nigel has a 1977 R100 RS, and his dad has a 1980’s era BMW. Someone else in the group has the new Royal Enfield Himalayan.

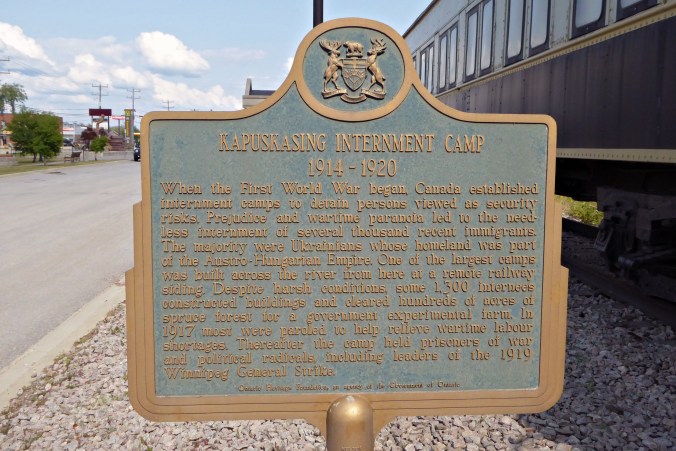

Surrounding the station were archival photos of the town and area, and I discovered that Kapuskasing had been the site of an internment camp during WWI. Primarily Ukrainian immigrants were shamefully sent there to work in a government-run experimental farm studying the viability of farming on clay. Later in the war it was a POW camp.

Surrounding the station were archival photos of the town and area, and I discovered that Kapuskasing had been the site of an internment camp during WWI. Primarily Ukrainian immigrants were shamefully sent there to work in a government-run experimental farm studying the viability of farming on clay. Later in the war it was a POW camp.

I used some cardboard and created templates that I could fit into the openings. They were basically squares but with the edges folded about 1/4″. I would use those edges to fix the grill to the shroud, but more on that later. I had to cut the corners so when folded they became like a box (or half a box). One opening on each side was a little tricky because one side of the square is not straight but has a jog. Carefully measuring and fiddling is necessary, but better to do this with cardboard before cutting into your grill.

I used some cardboard and created templates that I could fit into the openings. They were basically squares but with the edges folded about 1/4″. I would use those edges to fix the grill to the shroud, but more on that later. I had to cut the corners so when folded they became like a box (or half a box). One opening on each side was a little tricky because one side of the square is not straight but has a jog. Carefully measuring and fiddling is necessary, but better to do this with cardboard before cutting into your grill.

This is a little messy and you have to vacuum carefully afterwards to collect all the sharp bits of discarded metal. I then held the template against the cut metal and used my Workmate, my vice, and some blunt-nosed pliers to fold and shape the guards.

This is a little messy and you have to vacuum carefully afterwards to collect all the sharp bits of discarded metal. I then held the template against the cut metal and used my Workmate, my vice, and some blunt-nosed pliers to fold and shape the guards. I offered each into its opening and tweaked.

I offered each into its opening and tweaked.  This requires patience, but if you follow your templates as a guide, which you know fit well, you’ll eventually get there. Use the tin-snips or pointed-nose pliers to trim off or bend in sharp edges that can scrape the plastic as you fit them. If you do scratch the plastic a bit, use some Back to Black or Armour All to lessen the visibility of the scratch.

This requires patience, but if you follow your templates as a guide, which you know fit well, you’ll eventually get there. Use the tin-snips or pointed-nose pliers to trim off or bend in sharp edges that can scrape the plastic as you fit them. If you do scratch the plastic a bit, use some Back to Black or Armour All to lessen the visibility of the scratch. Fortunately, those clever German engineers had the foresight to drill two holes in the opposite side from the mounting points, probably with something like this in mind. When the guards are done, you can fix them into the shrouds using the mounting screws on the inside and either zip ties or 1/2″ 10-24 machine screws and washers on the outside. I decided to go with the screws just to be sure everything stays put.

Fortunately, those clever German engineers had the foresight to drill two holes in the opposite side from the mounting points, probably with something like this in mind. When the guards are done, you can fix them into the shrouds using the mounting screws on the inside and either zip ties or 1/2″ 10-24 machine screws and washers on the outside. I decided to go with the screws just to be sure everything stays put.

I’ve always said I love my little thumper, but if it’s done one thing for me it’s to get the off-road hook sunk deep. My first two years of riding have been a slow gravitation toward off-roading simply because the challenge and possibilities are endless. It’s also pretty exhilarating when you slide out the back end going around a corner on a gravel road, or charge up a rocky hill climb, or feel the bike slide around beneath you through some mud. The Africa Twin is the off-roader’s adventure bike. I sat on the Triumph Tiger 1200 and you know what? I wouldn’t want to be taking that beast off-road.

I’ve always said I love my little thumper, but if it’s done one thing for me it’s to get the off-road hook sunk deep. My first two years of riding have been a slow gravitation toward off-roading simply because the challenge and possibilities are endless. It’s also pretty exhilarating when you slide out the back end going around a corner on a gravel road, or charge up a rocky hill climb, or feel the bike slide around beneath you through some mud. The Africa Twin is the off-roader’s adventure bike. I sat on the Triumph Tiger 1200 and you know what? I wouldn’t want to be taking that beast off-road.  I imagine the BMW 1200 is the same. There’s just no room for error with all the weight. And don’t try to tell me you don’t feel the weight because it’s so nicely balanced. The first time you and the bike get kicked sideways off a large rock that rolls away from under you, you’ll feel the weight, all 580 lbs. of it as you lift it up. The Africa Twin, on the other hand, is 507 lbs., a full 73 lbs. lighter thanks to it’s smaller 999cc engine—more than enough to get you to the Timmies of your choice. But where the Africa Twin really shows its off-road colours is with the wheel size: 21” front and 18” rear. Compare that to 19” front and 17” rear in the R1200GSA and you know why the ground clearance is 9.8” compared to 8.5”. As far as I’m concerned, the 12000GSA is the bike for long adventures in remote areas, but I wouldn’t want to take it anywhere more remote than a dirt road. The 800GS is the true BMW adventure bike.

I imagine the BMW 1200 is the same. There’s just no room for error with all the weight. And don’t try to tell me you don’t feel the weight because it’s so nicely balanced. The first time you and the bike get kicked sideways off a large rock that rolls away from under you, you’ll feel the weight, all 580 lbs. of it as you lift it up. The Africa Twin, on the other hand, is 507 lbs., a full 73 lbs. lighter thanks to it’s smaller 999cc engine—more than enough to get you to the Timmies of your choice. But where the Africa Twin really shows its off-road colours is with the wheel size: 21” front and 18” rear. Compare that to 19” front and 17” rear in the R1200GSA and you know why the ground clearance is 9.8” compared to 8.5”. As far as I’m concerned, the 12000GSA is the bike for long adventures in remote areas, but I wouldn’t want to take it anywhere more remote than a dirt road. The 800GS is the true BMW adventure bike.

Only 250cc., you say? This easily does 120 km/hr. on the highway and tops out at 140, but if you’re riding a 250 you probably aren’t riding the highway anyway. Only as much as necessary. You can put a tail rack on this baby, some soft panniers, and hit the Trans-Am Trail, or The Great Trail in Canada, for that matter.

Only 250cc., you say? This easily does 120 km/hr. on the highway and tops out at 140, but if you’re riding a 250 you probably aren’t riding the highway anyway. Only as much as necessary. You can put a tail rack on this baby, some soft panniers, and hit the Trans-Am Trail, or The Great Trail in Canada, for that matter.  This little bike is a dirt-bike on steroids, capable of adventure too if you’re not in a hurry. And at only 235 lbs., it would be a fun and safe starter bike. The other option at Honda is the “adventure styled” CB500X.

This little bike is a dirt-bike on steroids, capable of adventure too if you’re not in a hurry. And at only 235 lbs., it would be a fun and safe starter bike. The other option at Honda is the “adventure styled” CB500X.  With cast wheels and a lowish ground clearance, this is clearly a street bike. But with the

With cast wheels and a lowish ground clearance, this is clearly a street bike. But with the  But then the silver, brushed metal tank is pretty cool too, harkening back to those old Norton tanks.

But then the silver, brushed metal tank is pretty cool too, harkening back to those old Norton tanks.  Or the one with black and gold highlights.

Or the one with black and gold highlights.  But my favourite, if we are posing, is the Racer with the retro colours and bubble cockpit. This would definitely turn some heads.

But my favourite, if we are posing, is the Racer with the retro colours and bubble cockpit. This would definitely turn some heads.

It tries too hard. The whole secret of a poser bike is getting one that looks great but not too great, if you know what I mean. It’s a sign of desperation. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never been drawn to Harley Davidson, and you’ll notice there are no photos here of them. The only photos I took at the Harley display was of the entire display, complete with rock music, large-screen video, lots of leather, and Harley chicks in skimpy skirts. They are clearly selling a lifestyle. It’s a sight to behold. But if I were forced to chose another bike, less practical than my adventure bike, but that looks great, I’d be more inclined to go with something like the Triumph T100 or the Street Twin. Classic, classy, and modern, all in one package.

It tries too hard. The whole secret of a poser bike is getting one that looks great but not too great, if you know what I mean. It’s a sign of desperation. Perhaps that’s why I’ve never been drawn to Harley Davidson, and you’ll notice there are no photos here of them. The only photos I took at the Harley display was of the entire display, complete with rock music, large-screen video, lots of leather, and Harley chicks in skimpy skirts. They are clearly selling a lifestyle. It’s a sight to behold. But if I were forced to chose another bike, less practical than my adventure bike, but that looks great, I’d be more inclined to go with something like the Triumph T100 or the Street Twin. Classic, classy, and modern, all in one package.  Triumph should be applauded for bringing back these classic bikes but seamlessly incorporating all the benefits of modern technology. And they get it right with the analog display, round headlight, and fork gaiters.

Triumph should be applauded for bringing back these classic bikes but seamlessly incorporating all the benefits of modern technology. And they get it right with the analog display, round headlight, and fork gaiters. The ergonomics are perfect and the seat is wide and comfy. Unlike BMW, Kawasaki have designed their way out of the comfort saddle aftermarket, to their credit. They know their clientele. Then he looked at the price: a little over $7,000. Compare that to the “comparable” 750GS at almost $11,000. That’s about $4,000 more, a lot of money when you are a student. Okay, the 310R, wherever it is, is $6,450, but has half the power and cast rather than spoke wheels. I’d take the KLR any day, but God-forbid not that ugly Camo version. What were they thinking?

The ergonomics are perfect and the seat is wide and comfy. Unlike BMW, Kawasaki have designed their way out of the comfort saddle aftermarket, to their credit. They know their clientele. Then he looked at the price: a little over $7,000. Compare that to the “comparable” 750GS at almost $11,000. That’s about $4,000 more, a lot of money when you are a student. Okay, the 310R, wherever it is, is $6,450, but has half the power and cast rather than spoke wheels. I’d take the KLR any day, but God-forbid not that ugly Camo version. What were they thinking?

Designed by a small, very specialized team, the bike is BMW’s pure-bred racer, and here was one of only 750 made. No wonder we were not allowed to sit on it. Back down on earth, we looped back around to Honda to look at the new Gold Wing.

Designed by a small, very specialized team, the bike is BMW’s pure-bred racer, and here was one of only 750 made. No wonder we were not allowed to sit on it. Back down on earth, we looped back around to Honda to look at the new Gold Wing.