2006 BMW f650 GS twin spark.

I’ve been reluctant to do a bike review of Bigby. For one, I still consider myself a novice. In fact, aside from a few bikes at my training school, Bigby is the only bike I’ve ever ridden, so I don’t have much to compare it to. Doing a review, I thought, would inevitably lead to the faulty comparison, a logical fallacy I warn my students to avoid. (i.e. “Gets your clothes cleaner!” Ugh, cleaner than what?) Second, I’m still learning about the bike. Although I’ve owned it for almost three years, I’m still finding my way around the engine and mechanics and still discovering its potential. Passing judgment now would be like bailing out of a relationship after the second date. It would be, in the literal sense of the word, prejudice.

So why have I decided to do it? Well, after watching a lot of reviews online, I’ve come to realize that most are not very good, so the bar is set pretty low. They are usually more product descriptions than reviews, and Ryan at Fort Nine has blown the whistle on the nepotism of corporate reviews, how they are always positive because the big bike companies offer a lot of treats to the reviewers, like paid vacations in exotic locations. And those reviewers ride the bike for, what, a day, a couple of days, max, so at least I can say that after three years with Bigby, I know more about this bike than they ever will. So with my concerns made explicit, let’s jump in.

* * *

The three things I like the most about the f650GS are three things I noticed within the first five minutes of riding it: ergonomics, suspension, and balance. Okay maybe you don’t need to have ridden a bike for long before you discover its essence. Let’s look at each in turn and then move on to other stuff.

Ergonomics: At the school, we’d learnt on cruisers—Suzuki Boulevards and Honda Shadows. The ergonomics of the GS are very different. Being a dual-sport bike, it’s capable of going off road, and you need the pegs beneath you in order to stand. This placement also results in your weight being distributed evenly between the seat and pegs, with knees bent at roughly 90 degrees. It’s the ideal sitting position and how every office chair should be set up, thus making the GS also a very capable touring bike. The dual-sport, according to its name, involves compromise, but there’s no compromise when it comes to ergonomics: the GS provides the perfect sitting position, and the capability to stand when you leave the asphalt.

The other thing I like about the ergonomics is that you can flat foot this bike. The standard seat height is 30.9 inches, so super low. This is confidence inspiring once you take it off road; I know I can easily dab a foot if needed. In fact, since I am rather long-legged, the seat was a bit too low; my knees were bent more than 90 degrees and I felt a bit cramped after several hours in the saddle. So when I upgraded my seat (more on this later), I went for the high version to allow a bit more room, and that has made all the difference. If you are long-limbed, you might want to look at the Dakar version, which has a 34.3 inch seat height, or swap the saddle for a taller one. Despite these issues in my lower half, I haven’t had to add bar risers, and when I stand, the grips fall perfectly to where I need them, maintaining my standing posture.

Suspension: As I rode off on my first ride, the second thing I noticed was the suspension. This bike is smoooth, at least compared to those cruisers. And what better place to test a bike’s suspension than Montreal roads! Of course it makes sense that a dual-sport bike would have very capable suspension; it’s designed to be able to handle some pretty bumpy terrain. But just before I went for my riding test, I hired a private instructor for a class. He rode behind me and commented on things he saw. Now here is someone who has a lot of experience with bikes and has seen a wide variety from behind. Ironically, the first thing he remarked when we first stopped had nothing to do with my riding but how impressed he was with the rear suspension of my bike. “I wish you could see what I see from behind,” he said. “It’s amazing!”

In fact, I’ve wondered if the suspension is a little mushy. I’ve only bottomed out a few times while off-roading, and the front end dives a bit under hard braking. I’ve considered upgrading the suspension, but frankly, at only 140 lbs, I’m actually underweight for this bike. Front suspension travel is 170 mm and rear is 165 mm. Since ideal SAG is roughly 30% of total travel, SAG for the 650GS is 49.5 mm.. Even with the pre-load completely backed off, all of my 140 lbs is putting a little more than 45 mm on the suspension. Which brings me to another plus of this bike: the pre-load adjuster. Okay, it’s not electronically controlled like the new Beemer’s, but the ability to adjust with the turn of a knob when you are two-up or have gear on the back is a nice feature.

Balance: The thing I like most about the 650GS is its balance. This is accomplished mainly due to the gas tank being under the seat instead of high on the bike where it normally is. Where this is most noticeable is in how the bike corners. At the school, we were taught to countersteer to initiate a turn and to accelerate at the end to straighten up, and this was necessary with those cruisers. But I quickly discovered that on the GS you can manage an entire sweeping curve simply by leaning in and out. It’s hard to describe, but the bike feels like it straightens up itself with the subtlest weight shift.

The balance also shows when riding at slow speed, like in parking lots or technical sections off road. I’ll challenge anyone to a slow race any day! The bike is easy to move around by hand and to turn in tight spaces. With a little practice, I was riding figure-eights full lock. You can add all the accessories you like to a bike, but getting the balance right is something that happens at the design stage. BMW got it right on this one, which is why I was surprised to hear that they’ve moved the tank to the traditional location in the hump on the 2018 750s and 850s.

* * *

The engine is a Rotax, 652 cc single-cylinder, water-cooled, DOHC with twin spark plugs and four valves. It provides 50 HP @ 6,500 rpm and 44 lb/ft torque @ 5000 rpm. What these numbers mean is that it’s not the gutsiest engine. I’m up for a slow race but I won’t be challenging anyone to a drag soon. When I did my research, I kept hearing how this bike is a good beginner bike. There’s not a lot of power to manage, and you don’t have to worry about losing the back end by getting on the throttle too hard. On the other hand, it’s got lots of torque down low in the first two gears for hill climbs off road, and still some roll on in 5th gear at 120 km/hr. I’ve never maxed it out, but I’ve had it up to 140 km/hr and that’s fast enough for my purposes. And since we’re talking about gearing, 3rd and 4th are wide enough to enable me to navigate a twisty piece of road pretty much in one gear, depending on the type of road: roll off going into a corner, roll on coming out.

Single-cylinder engines have their advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is this wide gearing. My dad often talks about how he loved this aspect of his 350 Matchless. In heavy traffic, you can stay in 2nd and just ease the clutch back out when traffic picks up again. He once road his brother’s parallel twin and said it was horrible in stop-and-go traffic; you had to work twice as hard to prevent the engine from bogging. I suspect it’s this same quality that allows you to maintain your gear through a twisty section of road with slight variations in speed.

Another advantage of singles, I’ve recently discovered in this article in Cycle World, is that they offer a kind of traction control. As Kevin Cameron argues, “no other design produces such forgiving power delivery under conditions of compromised traction without elaborate software.” This is due to the millisecond duration of the exhaust stroke with big-bore engines, when there is relatively little power delivered to the tire, allowing it to regain traction if it begins to break loose. It’s like anti-lock brakes, the theory goes, but in reverse. Compare that to the constant power delivery of multi-cylinder engines, which makes managing power and traction more challenging.

A disadvantage of single-cylinders is the vibration. The Rotax engine is about a smooth as a single comes, I’ve heard, but it can still make your throttle hand go numb, especially if it’s cold, so you might want to invest in a throttle assist or throttle lock. I have the Kaoko and it works great. Unfortunately, the Rox Anti-Vibration Risers don’t fit my particular bike due to the configuration of the triple-clamp, but then I’ve heard those can make the steering mushy, which can be unnerving when riding off road. And it might be my imagination, but it seems that there are less vibrations when using the BMW oil. It certainly seems that the engine runs quieter and smoother, perhaps not surprising given that BMW design and test the oil specifically for their engines. Speaking of oil, the Rotax engines do not burn oil. Ever. Don’t believe me, go ask the inmates at The Chain Gang, a user forum devoted to the BMW 650s.

On the other hand, it’s a major pain in the ass to do an oil change on this bike. Because the engine uses a dry sump system, there’s an oil tank on the left side of the hump where a gas tank normally would be (an airbox is on the right side), so draining the oil involves removing the left body panel and draining that holding tank, plus draining the pan by removing the sump plug at the very bottom of the engine. If you have a bash plate, as I do, you have to remove that too, which, if it’s attached to the crash cage . . . and so on, until you’ve stripped the bike halfway down. Or you can drill a hole in your bash plate as I did, which makes that job a lot easier. You’re still going to get some oil on the plate, and you’re going to get some on the engine when you remove the oil filter due to its recessed placement, so just have plenty of shop towels on hand.

My 2006 650GS does not have rider modes and sophisticated electronics. It doesn’t even have anti-lock brakes. At first I was concerned about this and it was almost a deal-breaker for this newbie. But I spoke to a few experienced riders and they all agreed: better to learn how to control traction and perform emergency braking using proper technique than rely on electronics. Since I’m rather a purist in most things, I understand that. If you learn to emergency brake by grabbing a handful of brake lever and letting ABS do its thing, you aren’t going to develop the feel needed to control sliding in off-road situations. And not having all that sophisticated electronics makes the bike easier to maintain.

The 650GS is fuel-injected so there is an ECU. A 911 diagnostic code reader is available to help you troubleshoot the electronics, but it’s expensive. One advantage of fuel injected bikes is that there is no choke to deal with, and the ECU adjusts the fuel-air mixture according to altitude, meaning you can literally scale any mountain without having to change the jets of a carburetor or risk running your engine hot. The downside is that the throttle can be a little choppy so easy on the roll-off.

Two areas where the 650GS is lacking are the saddle and the windscreen. The saddle is hard and slopes downward, so you always feel like the boys are jammed up against the airbox. If you plan on using your GS for long day trips, you’ll want to upgrade the saddle. There are many aftermarket models available, including BMW’s own Comfort Seat, but I decided to go with Seat Concepts which, for about $250 CAF, they will send you the foam and cover and you reupholster it yourself using your original seat pan. I’ve done a blog on this job so won’t repeat myself here.

One issue with this era GS is the windscreen. The OEM screen is so small it barely covers the instrument dash. There are many aftermarket screens available, but finding the right one is a difficult matter of trial and error. The windscreen issues on this bike are well documented, and if you have sadistic leanings, just search at f650.com for aftermarket windscreens, sit back, and enjoy. The reading is almost as entertaining as a good oil thread. In my own experience, the bike came with a 19″ National Cycle touring windscreen, which was a bit high for off roading and was directing loud air buffeting directly onto my helmet. I swapped it for a 15″ but that too was loud, so I added a wind deflector and that solved the buffeting but I thought ruined the bike’s aesthetic, so I ultimately landed on a 12″ sport screen by National Cycle that protects my torso but keeps my helmet in clean air. The problem is the shape of the front cowling that the screen screws into. It angles the screen too much directly toward the rider’s helmet, instead of the recent bikes that have the screen more upright. The quietest screen on the aftermarket is the Madstad screen. It has an adjustable bracket that attaches to the cowling, allowing you to adjust the angle of the screen. It also has that crucial gap at the bottom of the screen, preventing a low pressure area that causes the buffeting developing behind the screen. Unfortunately, it’s a little pricey, but the real deal-breaker for me is that Madstad use acrylic, and acrylic screens don’t stand up to the abuse of off-road riding. National Cycle screens are polycarbonate.

Aesthetics: I love the aesthetics of this bike! Even ugly babies are adored by their parents, but sometimes I’ll look at a more modern luxury touring bike with the engine completely covered in plastic and I’m glad my bike has its guts hanging out like a proper bike. And I like that it has spoked wheels, which are stronger for off roading and have a more traditional look. Someone once said to me, “I love your old-fashioned bike.” Hmm . . . I hadn’t thought of it as old-fashioned but didn’t mind the comment. There definitely is a raw, real motorcycle quality to the bike, yet has refinements like heated grips and the quality control and reliability you’d expect from BMW. It is the ultimate hybrid dual-sport: part dirt bike, part luxury tourer.

In conclusion: The f650GS is a confidence-inspiring little bike that is perfect for not only beginners but also anyone who prefers a smaller, lighter bike. There’s a movement these days toward smaller bikes, with many people looking at the big adventure bikes with derision for their impracticality off road. I say it really depends on the type of riding you want to do and where you plan to take the bike. Due to its size and weight, the 650GS can go some places that the larger bikes can’t, but the cost is in vibration and rpms at speed on a highway. If you’ve got large areas to traverse but want the capacity to go on dirt roads when needed, then yeah, go for the big 1200GS that is so popular. But if you’ve got time and want to explore deeper into those remote areas, then the 650GS is an excellent choice. I plan on keeping mine as long as possible.

* * *

Pros:

Ergonomics for dirt and touring; smooth suspension; very well balanced; reliable Rotax engine; sufficient hp and torque for light off-roading; fuel injected intake has automatic temperature and altitude adjustment; classic aesthetics

Cons:

Cost (upfront and maintenance; even parts are expensive for DIYs); saddle is hard and uncomfortable; windscreen is useless, hard to find a good aftermarket replacement; engine can be vibey; only 5 gears

Modifications:

If you’d like to see the modifications I’ve done on the bike to make it more dirt-ready, follow the link below.

Dirt Walkaround

If you’d like to see the modifications I’ve done to return it to street riding, click below.

Street Walkaround

How’d I do with my first review? Please comment and click the Follow button if you liked this post.

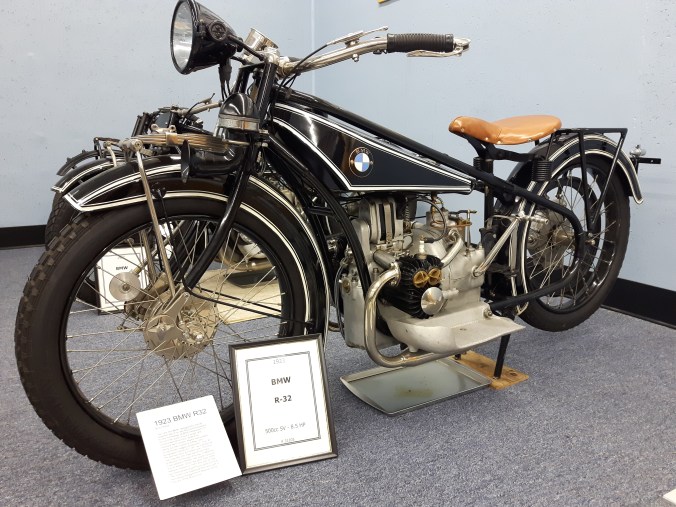

R-100S/5GS

R-100S/5GS

I used some cardboard and created templates that I could fit into the openings. They were basically squares but with the edges folded about 1/4″. I would use those edges to fix the grill to the shroud, but more on that later. I had to cut the corners so when folded they became like a box (or half a box). One opening on each side was a little tricky because one side of the square is not straight but has a jog. Carefully measuring and fiddling is necessary, but better to do this with cardboard before cutting into your grill.

I used some cardboard and created templates that I could fit into the openings. They were basically squares but with the edges folded about 1/4″. I would use those edges to fix the grill to the shroud, but more on that later. I had to cut the corners so when folded they became like a box (or half a box). One opening on each side was a little tricky because one side of the square is not straight but has a jog. Carefully measuring and fiddling is necessary, but better to do this with cardboard before cutting into your grill.

This is a little messy and you have to vacuum carefully afterwards to collect all the sharp bits of discarded metal. I then held the template against the cut metal and used my Workmate, my vice, and some blunt-nosed pliers to fold and shape the guards.

This is a little messy and you have to vacuum carefully afterwards to collect all the sharp bits of discarded metal. I then held the template against the cut metal and used my Workmate, my vice, and some blunt-nosed pliers to fold and shape the guards. I offered each into its opening and tweaked.

I offered each into its opening and tweaked.  This requires patience, but if you follow your templates as a guide, which you know fit well, you’ll eventually get there. Use the tin-snips or pointed-nose pliers to trim off or bend in sharp edges that can scrape the plastic as you fit them. If you do scratch the plastic a bit, use some Back to Black or Armour All to lessen the visibility of the scratch.

This requires patience, but if you follow your templates as a guide, which you know fit well, you’ll eventually get there. Use the tin-snips or pointed-nose pliers to trim off or bend in sharp edges that can scrape the plastic as you fit them. If you do scratch the plastic a bit, use some Back to Black or Armour All to lessen the visibility of the scratch. Fortunately, those clever German engineers had the foresight to drill two holes in the opposite side from the mounting points, probably with something like this in mind. When the guards are done, you can fix them into the shrouds using the mounting screws on the inside and either zip ties or 1/2″ 10-24 machine screws and washers on the outside. I decided to go with the screws just to be sure everything stays put.

Fortunately, those clever German engineers had the foresight to drill two holes in the opposite side from the mounting points, probably with something like this in mind. When the guards are done, you can fix them into the shrouds using the mounting screws on the inside and either zip ties or 1/2″ 10-24 machine screws and washers on the outside. I decided to go with the screws just to be sure everything stays put.