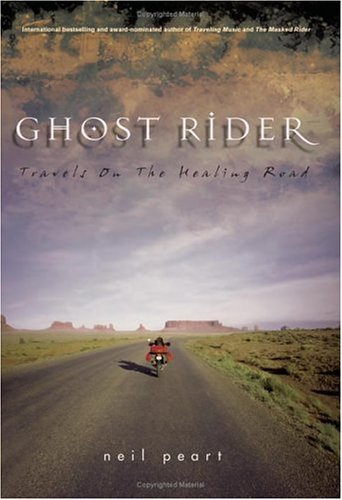

A review of Ted Simon’s Jupiter’s Travels: Four Years on One Motorbike

Before there was such a thing as an adventure bike, or the ADV industry, or a satellite tracker, or a cell phone, GPS, Google Maps, or even the internet, Ted Simon rode around the world. That was in 1973. At the time, he worked for The Sunday Times in England. They sponsored him and he wrote articles for them along the way, sending them back presumably by snail mail, before we called it snail mail. I would have been 10 years old at the time—a mere 50-odd years ago—and yet that world seems very distant now. The first thing I like about Simon’s book is that, like all classic literature, reading it takes you to another place and another time.

There are riders who can write, and there are writers who can ride. Simon is clearly of the latter. From the opening lines, he has us hooked, employing in medias res, a classical technique that dates back to Horace’s Ars Poetica (c. 13 BC) and means “into the middle of things.” We find Simon roadside and out of gas about fifteen miles outside Gaya, India, but by this point in his journey he’s discovered that he needn’t worry; things always find a way of working out. He’s already been on the road several years so has by this time learned what every experienced adventure rider knows: 1) to embrace the unexpected, and 2) to trust the goodwill of strangers. And so he waits . . . and in his waiting reflects on the years and miles behind him, and establishes for us the context. This writing may have started as an article for a newspaper, but Jupiter’s Travels is not a collection of articles. Simon knows how to structure a longer narrative.

He is rescued, of course, by two good samaritans on a Royal Enfield who accept nothing but a handshake and promptly take him to a Rajput wedding complete with dancing girls. If we weren’t already hooked, we are now. Simon’s description of one of them is so detailed, so lyrical, we know this is not going to be just about the ride.

The principal dancing girl held the floor most of the time. She was my favourite too, although her shape was far from my ideal. Her arms and shoulders were impeccable and moved with sinuous grace, and her face was full and pretty. The rest of her was wrapped tight in bodice and sari, but she proudly maintained an enormous and agile paunch, which seemed somehow to be much older than she was. I found myself watching it a great deal, amazed at the liberties it took, but distracted as I was by her belly I could not ignore her face. With true artistry she had created an expression of such supreme contempt for men that if I had been alone in a room with her I would undoubtedly have withered beneath her scorn. And just as surely, if it had softened towards me at all, I would have fallen into a state of deepest bliss. . . .

The dance itself was a strange and fragmentary thing, and at first I thought it quite ineffectual and hardly worth the ten-rupee notes that she peeled off her audience and passed to the tabla player. She would stand, tapping one hennaed foot, shaking the ankle bells, swaying to the beat, and arrange her body into one of several positions, perhaps a hip and shoulder pushing forward, legs slightly bent, head tilted to one side. Then, catching a particular phrase from the musicians, she would shuffle forward across the cloth, moving whatever there was to be moved (the belly moving itself in perfect harmony) for just six steps, before straightening up, letting her arms fall to her sides and sweeping us with a stupendous pout that said quite plainly ‘There, you bastards.’

In those six steps she said everything there was to say about men and women. (11-12)

The writing is like this throughout the 450 pages—observational, insightful, and eloquent—what travelogue ought to be. Ironically, sometimes it takes an outsider’s objective perspective to see into the heart of the matter. For instance, in The Triumph of Narrative, Canadian writer Robert Fulford makes the point that he can clearly see why the marriages of half a dozen of his friends failed but not his own; he’s too much on the inside. Similarly, as an outsider, the travelogue writer is sometimes able to see what others native to a culture cannot. Simon has this power of perception and we are its beneficiaries.

Sometimes, no insight is necessary when observational detail is so well captured. Like a moving picture without narrative or voice-over, Simon brings to life a streetscape by simply listing what he sees:

I went back to the Normandie, dumped the cameras, changed my swank jacket for a disreputable sweater and went out again determined to see something of Alexandria. Not far away, I found the sort of area I had been looking for, a poor working neighbourhood crammed with tiny lockup shops, people caning chairs, plucking chickens, bundling firewood, counting empty bottles, scooping grain out of sacks into small cones of thick grey paper, beating donkeys, dragging trolleys, recuperating scraps of everything under the sun. A small boy in rags, no, in one rag, had his capital spread on the kerbstone in aluminum coins and was counting it solemnly as though about to make an important investment. A number of delicate gilt chairs stood tiptoe on the pavement, like refugees from a revolution, having their seats stuffed. (72)

The listing of items without commentary or predication is called the cataloguing technique and can be traced back through Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (1956) to Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (1855). It’s a poetic technique that has an effect comparable to montage in film. Used selectively, as it is in Jupiter’s Travels, it can be incredibly effective in conveying realism since, come to think of it, what is our lived experience but a series of images, impressions, and snippets of dialogue which we render into a narrative in constructing meaning. Simon’s technique presents us with the raw material of life, place, and story.

Another aspect of the writing I admired was its daring honesty. For example, while riding through Sudan, he runs out of gas and, after being handed from one local to another throughout the afternoon and evening, finds himself late at night waiting with an Arab for a bus that would take them to Atbara, where he can purchase more gas. Neither speaks the other’s language so they wait mostly in silence, smoking cigarettes. The bus is due to arrive at midnight, and in the stillness and solitude of the desert at night, he is propositioned by the Arab in a way that is unmistakable despite the language barrier.

“Sudan signora queiss?”

I was still wondering about the question, when I felt a finger tap my thigh, and the voice repeated, with slight urgency:

“You Sudan Signora?”

. . . A little shudder of excitement ran through my body, because I knew, at that moment, that I could not be sure of my responses. The strange emptying effect of the desert seemed to have drained away all my conditioning. I did not know whether I was young or old, wise or foolish, strong or weak, and perhaps I did not even know whether I was male or female. But I did know that the tap on the thigh had released a current of sexual energy, and this invisible figure close to me had become mysteriously potent. . . .

This is a moment when you have absolute freedom of choice. Morality has blown away into the desert, you are not accountable to anyone. This is a privilege you have never allowed yourself before. So, do you want a sexual adventure with this man? (90-91)

Simon ends up declining, but the moment of reflection and self-awareness is revealing and could very easily have been edited from the manuscript once back in priggish England. Instead, Simon leaves it in as testament to the transformational power of travel. When exploring the world, we are not just discovering the world but previously unrevealed aspects of ourselves as well. Pushed out of our comfort zones and placed in unfamiliar and sometimes challenging situations, we broaden our inner as well as outer horizons.

Of course, his trip is not without drama. At one point, he loses his wallet containing his driving licences, vaccination certificates, credit cards, photographs, currency, and an all-important address book. In Brazil, he is arrested and incarcerated for weeks, convinced at times that he will be beaten or worse. He meets a woman named Carol at a commune in California and they live together for a blissful summer. They’re deeply in love and there’s a strong sense that Simon could have very easily abandoned the rest of his planned trip and spent the rest of his life with her. Perhaps it’s only his original commitment to the journey that pulls him away from her.

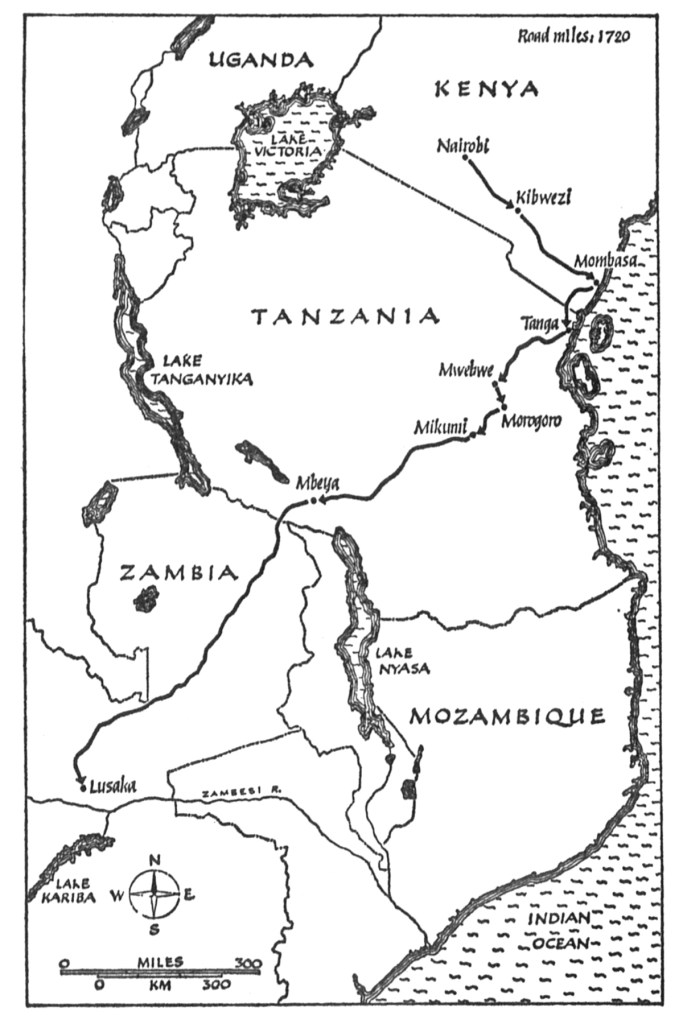

Simon’s tour is over 63,000 miles in 4 years and covers 54 countries on 5 continents. He begins in London, UK, and heads down through France, Italy, Sicily, and over to North Africa before heading east to Egypt. He then rides down the east coast of Africa to South Africa, crosses to Brazil, and rides up through South America to Los Angeles before crossing the Pacific Ocean to Australia. The final leg takes him through Thailand, Malaysia, then India, and across the Middle East back to England. Each section is headed by a simple black & white map showing his route, which seems appropriate for the book.

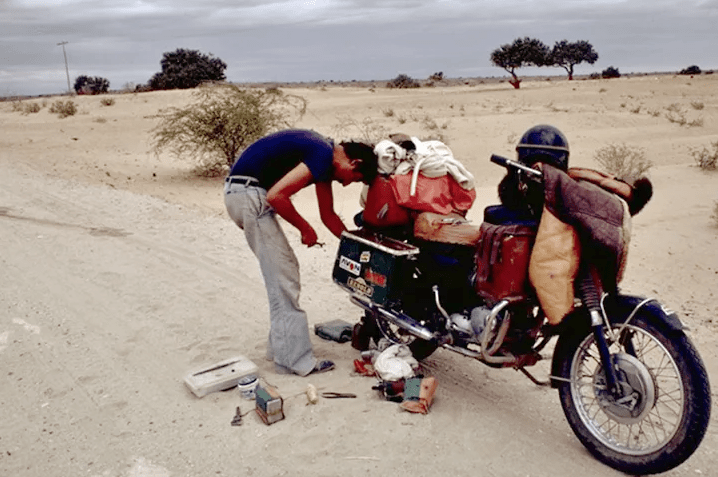

He rides a 1973 Triumph Tiger 100, which makes his accomplishment all the more admirable. To ride around the world on a motorbike is one thing, but to do it on a 1970’s era British motorbike is quite another; they were notorious for unreliability, and he has several breakdowns along the way. But in typical Pirsig fashion, he’s able to fix the bike and keep moving, although some parts are hard to come by and there are delays as he waits for parts to ship from England. In the end, we have to hand it to both Triumph and Simon: 60,000 miles of hard ADV riding on a bike of that era speaks for itself. The bike is now in The Coventry Transport Museum and appears in its original state as delivered by Simon upon his return to England in 1978.

The bulk of the book covers his travels in Africa and South America, with less detail in the rest of the trip. For this reason, my only criticism of the book is that it feels unbalanced and a bit truncated, as if the journey should have been covered in two books. Indeed, a sequel, titled Riding High, was published in 1998 and contains more stories that could not fit in Jupiter’s Travels. Perhaps it would have been better to plan the account over two books instead of rushing the ending of the first, but I understand the restrictions of book publishing and how the second probably grew organically out of the success of the first.

People often suggest to me that I should develop my YouTube channel and provide there full videos of my journeys, not just snippets to be embedded here in blog posts, and I’ve certainly considered it seriously. YouTube is where the money’s at these days, and I know from observing my students that reading is on the decline and video is ascending. Some of my more cynical colleagues say we are living in a post-literate society, and when I hear that youth today spend on average six hours a day on social media I can’t help thinking that there is some truth to that or there soon will be. But then I look at a book like Jupiter’s Travels and my confidence in the written word is reaffirmed. It’s the book that inspired Ewan and Charlie to do their Long Way Round tour in 2004, and the rest is history. It continues to inspire others to set out on their own adventures, whether big or small. According to Allied Market Research, the adventure motorcycle market was valued at $31.8B in 2022 and is projected to reach $64.5B by 2032.

But it’s not about the money. In Jupiter’s Travels, Ted Simon taps into something primal and lacking in our modern world, at least in western society. It would be too facile to say “freedom,” although that’s certainly part of it. He writes at one point that he would always rather be riding in heavy rain than sitting dry at home. Similarly, “risk” is attractive to those of us living rather staid, comfortable, cubicle lives, and there’s plenty of trials and tribulations for Simon during the four years. Some argue that risk is the essence of ADV riding (hence the jab about riding your BMW GS to Starbucks). But to understand the effect of a book like this we need to go deeper. What in it compelled Charlie and Ewan and countless others to break the pattern of their lives, sometimes at great personal and financial cost, and ride round the world (RTW), an act now so common it has its own acronym?

I think the answer to that question can be found in a word—adventure—the word that coined the industry. Stemming from the Middle English and Old French aventure, advent -ure, “adventure” has at its root “advent”—yes, that advent, the coming of Christ in the weeks leading up to his birth as Saviour of the World, but also ecclesiastically “his Second Coming as judge, and the Coming of the Holy Spirit” (Oxford English Dictionary). It’s the third of these that I think is the most relevant. What else would compel someone to endure the hardships and insecurity of long-distance travel on a motorcycle but to be in search of some sort of religious experience, to be fulfilled not by the creature comforts of consumerism but something else—a feeling, a spirit. I’m going to suggest that Jupiter’s Travels speaks to a hunger in the adventure rider, a desire to be connected to all things and everyone, even if we have to travel around the globe to find it. We may not be Sir Galahad in search of The Holy Grail, but our horses are made of metal and we are on a quest.

Click on any image for full size. Photo credits// top: Secrettrips.com; bottom L to R: ADVPulse & Overland Magazine