It wasn’t the tour I had planned, but the best adventures rarely are.

The original plan was finally to ride The Blue Ridge Parkway down into West Virginia and then take the MABDR and NEBDR back to Canada. Followers of this blog will know I’ve been trying to do this bucket list ride for the past several years, but something always gets in the way. This past season it was the ridiculous rhetoric coming out of President Trump’s mouth about Canada being the 51st state. Statements like that are disrespectful toward all Canadians at best and mildly threatening at worst. Despite how much I was looking forward to that tour, I decided to exercise what little agency I have as a Canadian by participating in the boycott.

I got to thinking that, while we don’t have BDRs here in Canada (yet), we do have the TCAT (Trans Canada Adventure Trail), and it’s the same idea. I thought I might do the section named The Forest that goes from Baie Comeau, Quebec, west to Kenora, Ontario, so essentially across the two largest provinces in Canada, mostly off road. The TCAT takes you through some very remote regions and would have been quite a challenge, especially solo.

Why solo, you ask? Well, it wasn’t for lack of trying. I put the word out to my riding buddies, but there was none who could get away from work and family commitments for the length of time I was considering, and others who could but had other stuff get in the way. I’m used to touring solo, although this would be the first time solo off road, which is never advisable. It’s always better to ride with a buddy, but if I got into trouble, I had a Garmin inReach Mini to help get me out.

Then my riding buddy Riley reminded me of the TQT, the Trans Quebec Trail. Same idea but closer to home and, more importantly, with an accompanying app. The concern I had with the TCAT is whether the tracks would be up to date. I’d come across this liability before when doing a section of it south of Calabogie, Ontario. A bridge was out but not indicated in the tracks I purchased, and this led to being stranded on a hydro line overnight. However, the TQT has an app and users can report a problem easily in real time, so you know the route is kept current. The app also includes information on gas stations, restaurants, campgrounds, accommodations, hospitals, and more, taking a lot of the burden out of this aspect of touring and providing some support and peace of mind. That decided it: I’d ride as much of the TQT as I could.

On the shakedown ride, the Tiger started having intermittent starting issues—not the usual slow-crank kind but a new no-crank kind—nadda, nothing. After a few minutes, it would crank and fire fine so the problem was clearly heat-related. Given where I was going, I decided to rig up a jumper cable from the starter terminal to up under the seat by the battery. If the bike started acting up in the middle of nowhere, I could bypass the ignition system by touching it to the Pos terminal of the battery.

My departure date arrived and I was loaded up and ready to go. Unfortunately, despite my best efforts to avoid a duffle bag on the tail, in the end I needed it because I was trying hammock camping and needed the room for an insulation pad that goes under the hammock. The duffle, however, was very light, containing the pad, my sleeping bag, and a few other items. It looks worse than it was.

I bombed down to Magog where I planned to pick up the TQT—2 hours of highway riding east of Montreal. It was hot, very hot, maybe not by Nevada standards but enough to make my phone battery overheat. When I reached the route, it took me some time to orient myself with the app. That involved some starting and stopping at the side of the road as I fiddled with my phone, and on one occasion, the bike wouldn’t restart, the same problem I was experiencing before. I figured it was because the lithium battery in the bike, like in my phone, was overheating, a problem I’d experienced before with another lithium battery. Using the jump wire, I found that the starter cranked just fine but the bike didn’t start. It was like it wasn’t getting any fuel. Not good. (At the time, I guessed that the ECU must need power to regulate the fueling, but I discovered much later that the issue was actually a loose wire into the fuel pump relay.) With the entire three weeks of remote riding ahead of me, I decided to err on the side of caution and return home.

The next day I started out again, this time with an old AGM battery in the bike. I rode again hard down to Magog, then stopped and started the bike several times, stressing the bike to test it as best I could before committing to the tour. It seemed to be starting fine now so on I went.

With these glitches behind me and the bike running great, I could finally enjoy the ride, and enjoy I did! I’ve never been east of the Townships up into the Mégantic Mountain Range but this region is beautiful. I passed through rolling hills and farmland in the valleys. The riding is not technical but mostly hard-packed dirt and gravel, which is good if you’re fully loaded.

The Tiger is perfect for this stuff, and since putting a Mitas Enduro XT+ on the front, the front end is planted, giving me a lot of confidence compared to when I had an Anakee Wild washing out on me.

As you can see, I was climbing up into the mountains as I headed northeast. The time came to start looking for a camping spot for the night. This is where the app is really helpful. It automatically detects when you are on the route and brings up sidebar information like next gas station, nearby attractions, and other options. One option is Campgrounds, and pressing it brings up nearby campgrounds relevant to your geolocation. I saw there was one a few kilometres away and pressing on it gave me the option to navigate there in the app of my choice. Nice! I might be explaining this slightly wrong, but trust me, it’s easy, and the next thing I knew I was pulling in to Camping Mont-Mégantic.

When the sun went down, it wasn’t long before I was in my hammock, enjoying listening to the rain on the tarp.

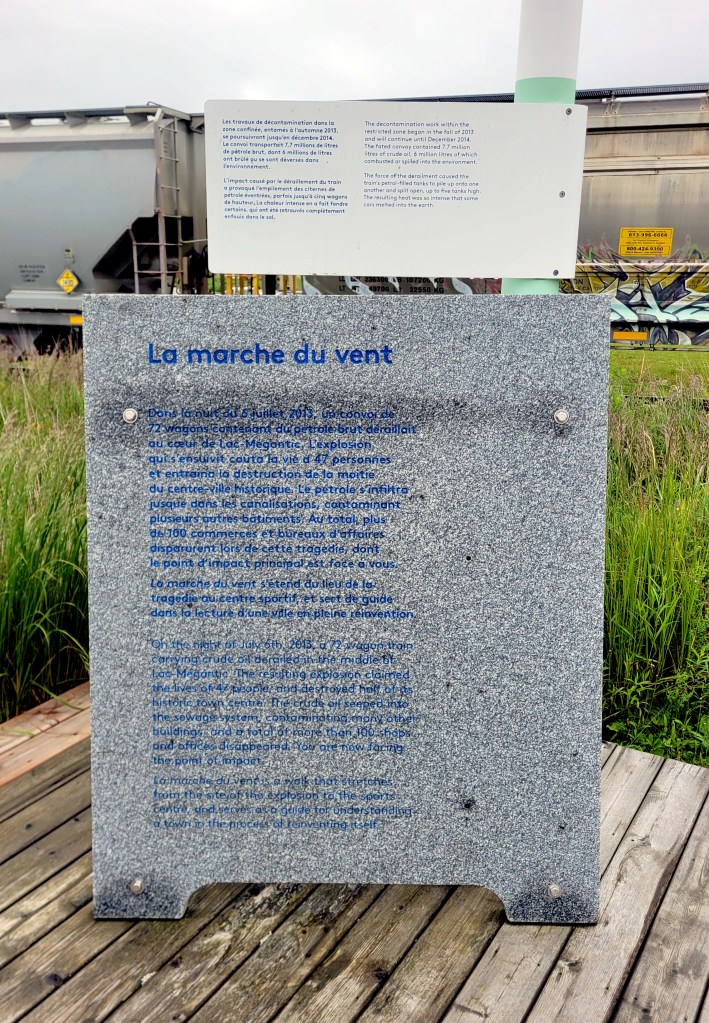

The next day started with a ride down into the lovely town of Lac-Mégantic. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because the town is the site of one of the worst industrial disasters in Canadian history. I soon found the memorial at the place where the accident occurred.

The inscription is a little difficult to read in the photo above so I’ve transcribed most of it below.

On the night of July 6th, 2013, a 72 wagon train carrying crude oil derailed in the middle of Lac Mégantic. The resulting explosion claimed the lives of 47 people and destroyed half of its historic town centre. The crude oil seeped into the sewage system, contaminating many other buildings and a total of more than 100 shops and offices disappeared. You are now facing the point of impact.

It was a moving and reflective moment, and I will admit, the feeling that came to me at the time in addition to sadness was anger, not at the oil industry or the railway workers. The accident was just that—an accident—and I’m not going to fault anyone for being human. No, my thought went to environmentalists who think they can solve our oil dependency by blocking pipelines. As I write this, about one third of global energy consumption is oil, and while it’s slowly dropping, we are still very much in need of moving oil across geography. Blocking a pipeline from being constructed, however well intentioned, does not erase the need. The oil is simply moved by freight instead, sometimes through populated areas like Lac Mégantic. Oil passes less than a few hundred meters from my house.

I don’t have the space here or the expertise to wade into the renewable versus fossil fuel debate. What I will say, however, is that blocking pipelines is short-sighted. A pipeline like the Trans Mountain Pipeline is an easy target, the proverbial line in the sand, but getting Alberta’s oil to global markets means Canada is less reliant on The United States as its sole buyer and can demand international market prices. More importantly, according to one study by the National Bank, getting China and India off of coal will reduce more CO2 emissions than what Canada produces as a whole. In fact, transitioning China alone off of coal will eliminate 8 times the amount of CO2 that Canada produces.

Of course, none of this was in my head as I stood at the site of the disaster and tried to imagine the devastation that the explosion caused, but I was thinking of the Quebec Government’s opposition to the Energy East pipeline proposal. Recently under increased demand for inter-provincial cooperation and trade, there has been a softening. The issues surrounding proposed pipelines are nuanced and complex, but my hope is that decisions are made based more on pragmatic calculations than political ideology or regional interests.

As I stood on the platform, a train carrying oil slowly passed through town, and it seemed to me that families came to witness it. The train was somehow central to this community, part of its collective memory and culture. The marche du vent is a walk that serves “as a guide for understanding a town in the process of reinventing itself,” and I was glad that a moment of reflection at this historic site was a part of my adventure.

I climbed back onto the bike and burnt some more fossil fuels. At times, the route narrowed to single-lane road so I had to keep my speed down and ride right.

I stopped in Saint George for lunch, then continued on northeast through the Beauce. This region is surprisingly still part of the Appalachian Mountains and the route seemed to zig zag back and forth across mountain ranges, providing a lot of fun riding and some spectacular views.

My planned destination for the day was just south of Rivière du Loup, where a friend has some property, but my progress was slow. You can’t really get out of 3rd gear on these roads, nor would you want to. In some sections, the route narrows further and becomes sandy, and there were other delays.

As the afternoon progressed, I had a decision to make: whether to start looking for a campsite or to bail on the TQT and get to my buddy’s property where he said I could pitch. I was curious to see his property and the log cabin he was building there, and I was ready to get out of the forest and nearer the coast, so I decided on the latter. 90 minutes of highway riding later, I was there just as the light was beginning to fade. Unfortunately, I happened to be there in one of the rare times that he was back in Montreal.

In the morning, I could see that Mark had the foundation poured. He now has the walls up and the roof on, hydro in, and windows and doors installed. That’s pretty impressive for one summer’s work, given that he’s virtually working alone with only his wife to help and provide food services. The only thing he didn’t get to was the chinking, so that will have to be done in the spring. (He has the cabin insulated though.) If you want to see how he’s done most of this construction and other work, check out his YouTube channel, Fierce Tartan. There you will see the nearly-finished project and how he managed to lift those huge beams into place on his own.

The workshite. As with most construction, it’s pretty messy and all comes together at the end.

I decided to stay a second night so I could rest a bit and enjoy the area. I went up to the local public beach for a swim, then rode into town to buy a cheap polar blanket because, even with the insulating pad, I wasn’t warm enough at night.

I had mixed feelings about bailing the day before. I tend to get goal fixated and not riding all the TQT to RDL felt like a fail. Honestly, what concerned me was the ZEC section I was heading toward, just south of La Pocatière and Kamouraska. ZECs are nature reserves and there really isn’t anyone in them this time of year when it’s not hunting season. The route skirts the US-Canada border east to Pehénégamook before turning north toward Rivière du Loup. That section looks really interesting as it follows the Notre Dame Mountain Range but would have to wait until I could return with some riding buddies.

After a McD’s breakfast, I followed my nose and found what I was looking for—a sunny, grassy, spot on the shoreline where I could read and nap in the shade. This is technically still the St. Lawrence River but you can see there is a tide. The water begins to become brackish, and just east it widens into the gulf.

After two days of boreal forest, this is what I was craving and was happy that the route east follows the shoreline a short ways before turning inland again. The next day’s riding took me through more small towns, some with unusual attractions.

But mostly it was more and more forest on gravel roads, and some of it quite remote.

The route now was taking me deeper into the bush and at the same time it began to rain. I decided again to detour off and go back to the coast. By the time I reached Bic, just west of Rimouski, it was pouring so I decided to splurge on a room for the night. Okay, call me a wimp, but one of the gifts of ageing is good judgment.

The Auberge des Îles du Bic was constructed in 1840. Rates were very reasonable and came with breakfast. The owner let me borrow the outside tap to hose down my bags before bringing them into the room.

The next morning I went exploring. I’d heard about Parc national du Bic and I was hoping to get a campsite there. Unfortunately, the campground is popular and they had no open sites. A neighbouring private campsite wasn’t very nice, and I was having trouble finding trees near the shore to string a hammock. At the same time, I was coming to some conclusions about the tour thus far.

For one, I wasn’t enjoying the solo touring as much as I had in the past. The shakedown ride with the boys on The Timber Trail in Kawartha Lakes was really fun and I was missing that camaraderie. Or perhaps I was now used to having Marilyn riding pillion. When I’d toured solo before, it was on the street where you run into people and are approached in coffee shops and gas stations. At any rate, riding solo for hours during the day through remote forest was lonely.

I also found that, while the off-road route involved potentially more interesting riding, I had to ride conservatively because I was alone. I didn’t feel comfortable venturing hundreds of miles into a nature reserve alone, and I was having some difficulty finding wild camping or campgrounds where I could string my hammock. Aside from the last few hundred kilometres into Rivière du Loup, I’d accomplished my primary goal of riding the TQT from Magog to Rimouski.

It was sometime around then that I decided to change my plans for the remainder of the tour. I would visit a good friend in central Nova Scotia instead and spend the following week touring that province’s western coastline, a region I’d never fully explored before. It would mean more asphalt and more tourists, but also more cafes, bookshops, and microbreweries. I will definitely be back on the TQT next summer and hope to go further, into Gaspesie and over the Chic-Choc Mountains. Next time I will come with friends.

Do you have any thoughts about my decision? Itchy Boots and Lyndon Poskitt and many other ADV riders ride solo. Am I getting old and soft or old and wise? The solo versus group tour debate is an interesting one. What is your preference? Drop a comment below and click Follow if you want to hear how the rest of the tour through NS goes.